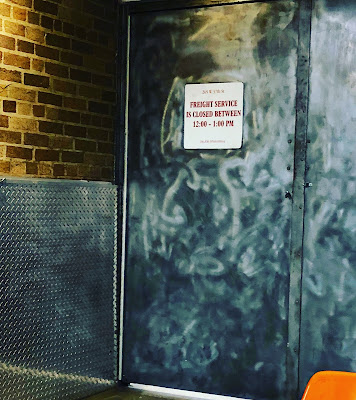

I exit the sidewalk off West Thirty-Seventh Street and duck into the freight entrance of number 236, exchanging a knowing look with the man by the laundry cart and sidling past the UPS guy’s trolley. Pulling open the second pair of industrial doors, I feel like a member of Club El Sabroso, a diminutive lunch counter tucked into the back corner of this building’s loading dock.

El Sabroso is wedged between a newsstand and a coffee shop. A couple of faded signs and menus give a nod to its presence, but among the cacophony of the Garment District—with its windows crammed with bolts of fabric, its trucks disgorging racks of evening gowns—this is one place that’s not trying to lure you in.

At the six-seat counter, a few men in work jackets perch on mismatched stools, hunched over plates of meat and rice. No one speaks; the only sounds are the scraping of plastic forks against styrofoam and the buzz of a small TV propped in the corner, playing daytime soaps. In the far corner, a few messengers sit on boxes by an empty hand truck, waiting, waiting. Waiting is what you do in a freight entrance, after all—unless, that is, you happen to be eating your lunch.

El Sabroso has a basic setup: a few pots and some burners, a Bunn coffeemaker, boxes of Swiss Miss and instant oatmeal wedged between stacks of cups and napkins, a metal gate that rattles down after hours. It’s presided over by Tony Molina, who, like his restaurant, manages to be both welcoming and taciturn. Patrons know the routine and require few words, in English or Spanish. The offerings are basic Latin American comfort food: a selection of meats so tender they fall off the bone, all served with yellow rice and beans and “salad” (shredded iceberg lettuce). There’s a fridge with sodas—no diet options here. As a vegetarian, I order rice and beans and a fried cheese empanada, then find a seat at a folding table.

The empanada is a hollow slab of fried dough filled with a few chunks of mild melted cheese, but the rice and beans are superlative: firm, salty beans that melt into softness, moist grains of chewy, buttery yellow rice in satisfying clumps, all offset by the shards of crisp and cool lettuce. I heap on the smoky hot sauce from the communal tin pot: it injects tangy heat into each bite.

The concrete floor is streaked with wheel marks from carts rounding the corner. This is, above all, a place of transition. But to El Sabroso’s loyal customers—who include construction workers in hard hats and office workers in cardigans—it is a still point of calm and comfort.