Poetry to Ease the Final Passage

January 27, 2017

“We all have to face this thing sometime,” my wife’s father, Lucas Dargan, told me around the time he turned ninety-nine.

Six months later, he found himself facing precisely that “thing.” A retired forester who planted over two million trees in his lifetime, he had split wood every morning until two years before.

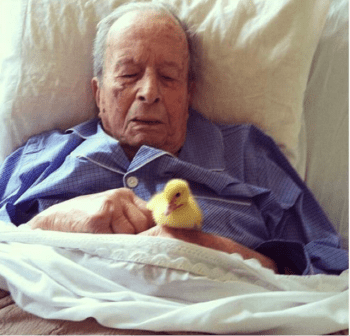

Photo by Sarah Dargan

Tonight, he lay in a hospital bed at the McCleod hospital in Florence, South Carolina, unable to properly swallow or get out of bed unassisted. Family members took turns staying overnight with him, and this night was my turn. At one point, I thought he was sleeping. I was working on my computer, when I heard lines from a poem coming from the other side of the room:

I am dying, Egypt, dying

Ebbs the crimson life-tide fast,

And the dark Plutonian shadows

Gather on the evening blast

“I think it’s from Shakespeare,” he told me, so I brought my laptop over to his bedside and looked up the lines. Born in 1917, Lucas was always amazed at the magic of the Internet to access any tidbit of knowledge. The verse turned out to be from a poem by William Haines Lytle inspired by Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra. The first line, “I am dying, Egypt, dying,” is from the play itself. We then looked up the drama online and found Marc Antony’s soliloquy that begins with that line. Then I read to him from Shakespeare’s play.

Photo by Rosa Dargan Powers

When I finished, he said, “Steve, when I close my eyes I think of the billions of people who have done this before me.”

“Well, you know you’ll be remembered,” I said.

“That’s true,” he said, “not as good as heaven—but a lot better than hell.”

The next day the doctor told Lucas and the family that there was nothing more to be done medically and recommended hospice care. That day, we brought Lucas home to the family farm and set up his bed in the living room, where for the next three weeks he was surrounded by family members and a stream of visitors, including guests for the weekly poetry and music nights he had hosted at the house for many years. Other visitors included members of his old Boy Scout troop, who talked about what they had learned from him, and a local farmer, David White, who had started a tradition of bringing lunch to share with Lucas every Monday, and who this time brought in a newborn duckling on his visit.

Among his many visitors was the hospice chaplain with whom Lucas couldn’t help but share his view of religion: “I do not claim to understand the nature of the Supreme Being, and I do not acknowledge that anyone else does either.” Lucas was a devoted agnostic who believed that it was just as much a leap of faith to be an atheist as a believer. The chaplain, who returned for a second visit, said he enjoyed discussing spirituality with Lucas and concluded, “He just doesn’t want to put God in a box.”

It was clear to all of us that in his final days Lucas sought solace in poetry, not religion. He told my wife Amanda, “I think all poets share a deep concern for the human condition.” And the poets whose works he wanted to hear or to recite were those who wrote about death and dying and those whose poems he had memorized when he was young.

Many of the poems he knew by heart, including some we had never heard him recite before. Once, when I asked if he wanted me to read a poem, he said, “Steve, look up Carruth.”

“Carruth?” I said.

“Yes, C-a-r-r-u-t-h, William Herbert Carruth.”

The poem he had in mind, “Each in His Own Tongue,” seemed to capture Lucas’s poetic perspective on religion. I picked up his tattered copy of One Hundred and One Famous Poems, published in 1924. I read a line from the poem, A haze on the far horizon. Lying in his bed, he recited the second from memory, The infinite, tender sky. I read the third line, and then he responded with the fourth from memory. We went all through the poem in tandem.

The ripe, rich tint of the cornfields,

And the wild geese sailing high—

And all over the upland and lowland

The charm of the goldenrod—

Some of us call it Autumn,

And others call it God.

A day or two later, he asked Amanda to read the poem “Thanatopsis” by William Cullen Bryant, another classic nineteenth-century poem about death.

. . . When thoughts

Of the last bitter hour come like a blight

Over thy spirit, and sad images

Of the stern agony, and shroud, and pall,

And breathless darkness, and the narrow house,

Make thee to shudder, and grow sick at heart . . .

As she read, Amanda watched her father close his eyes. She thought he had drifted off to sleep, and she put the book down, too sad to continue. When he opened his eyes a few minutes later, her sister Rosa asked, “Would you like to hear another poem?”

“Not yet,” he said. “Amanda hasn’t finished the one she was reading.”

Rosa finished reading Bryant’s poem.

So live, that when thy summons comes to join

The innumerable caravan, that moves

To that mysterious realm, where each shall take

His chamber in the silent halls of death,

Thou go not, like the quarry slave at night,

Scourged to his dungeon, but, sustained and soothed

By an unfaltering trust, approach thy grave

Like one who wraps the drapery of his couch

About him, and lies down to pleasant dreams.

Lucas draped himself in the weave of his favorite poems as he confronted death, as if he could pull them up like a blanket. They kept him warm and clearly helped him approach his death with peace of mind. His amazing mind—“fastened to a dying animal,” as Yeats put it—remained sharp until the end. He didn’t stop reciting and listening to poems until the day before he died. “We should all aspire to his life—and his death,” his nephew Rod McIver said.

As befitted this man, his daughters planned the funeral service to include his grandchildren reading some of his favorite poems, including Shelley’s “The Cloud,” Masefield’s “Sea Fever,” and Tennyson’s “Crossing the Bar.” The service closed with his poetry-night stalwarts—Stanley Thompson, David Brown, and Worth Lewellyn—playing his favorite song, “Loch Lomond,” on fiddle and guitar. (“You take the high road and I’ll take the low and I’ll get to Scotland before you . . . ” )

I was left mulling over the lines we had read together from Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra.

This case of that huge spirit now is cold . . .

And there is nothing left remarkable

Beneath the visiting moon.

~Steve Zeitlin

6 thoughts on “Beneath the Visiting Moon”

Wonderful tribute to Mr Lucas Dargan

The reference to Shakespeare’s play brought the poem below to mind. The poet, C.P. Cavafy, is one of my favorites. He is considered one of the greatest modern Greek poets.

Background: The poem refers to Plutarch’s story of how Antony, besieged in Alexandria by Octavian, heard the sounds of instruments and voices of a procession making its way through the city. The god Bacchus (Dionysus), Antony’s protector, was deserting him; According to Plutarch, Bacchus abandoned Antony the night before Alexandria was conquered by his enemies. The poet urges Antony not to mourn his fate, but to face the losses of his God, his city and his lover (Cleopatra) with grace and courage.

The God Abandons Antony

At midnight, when suddenly you hear

an invisible procession going by

with exquisite music, voices,

don’t mourn your luck that’s failing now,

work gone wrong, your plans

all proving deceptive—don’t mourn them uselessly:

as one long prepared, and full of courage,

say goodbye to her, to Alexandria who is leaving.

Above all, don’t fool yourself, don’t say

it was a dream, your ears deceived you:

don’t degrade yourself with empty hopes like these.

As one long prepared, and full of courage,

as is right for you who were given this kind of city,

go firmly to the window

and listen with deep emotion,

but not with the whining, the pleas of a coward:

listen—your final pleasure—to the voices,

to the exquisite music of that strange procession,

to say goodbye to her, to the Alexandria you are losing.

–C.P. Cavafy

So beautiful. I met Lucas once, and have heard him praised by many family members. Someone posted a picture of him as a young man, a very handsome young man.

It is such a loss to have Lucas pass, He reminds me of my uncle Hinky ( Henry Louis Ware ) in his love of poetry and remembering every line of the most loved ones.

As an agnostic, also like Hinky, he may be very surprised when he reaches . Heaven

So beautiful. I met Lucas once, and have heard him praised by many family members. Someone posted a picture of him as a young man, a very handsome young man.

It is such a loss to have Lucas pass, He reminds me of my uncle Hinky ( Henry Louis Ware ) in his love of poetry and remembering every line of the most loved ones.

As an agnostic, also like Hinky, he may be very surprised when he reaches heaven

So beautiful. Do you suppose that our next generations will read our poetry which, I think, is the song of the soul?

I think they will if we help them! I plan on reading poetry with my baby 🙂