Poetry of Everyday Life Blogpost #25

Produced in collaboration with Voices: Journal of New York Folklore

As the Founding Director of City Lore, an urban cultural center in New York, and the husband of folklorist Amanda Dargan, who comes from a close-knit family and community of cousins in the rural Pee Dee region of South Carolina, I have both urban and rural connections. The rural connections run along two intersecting roads, South Charleston Road, the first road designated as a “Scenic Byway” in South Carolina, and Pocket Road, where the Back Swamp community of cousins live. The extended family, all connected through the Ervins and Dargans, has lived on and farmed the land for generations.

Much of the land in the community is protected through conservation easements held by the Pee Dee Land Trust “to ensure that the land will be available for farming, forestry, and recreation for future generations.” But in the past year, the community of cousins and their neighbors on Pocket Road have been threatened by development of the area where the road ends near I-95. The construction of a Bucees Box Store, a 53,000 square foot convenience and retail store with 120 fuel pumps, has made a patch of undeveloped land soar in value, and the cousins who co-own the land were offered about ten million dollars by a development company, most likely for yet another big box chain store that could destroy the quiet rural lifestyle of the families living on Pocket Road.

As one relative who lives closest the Buccees and Pee Dee Electric Cooperative building said, “I was planning to leave my home to my children. Now I worry that they won’t want to live here.” Money doesn’t just talk it screams. How could they possibly resist the temptation to sell, especially when the process of development has already started, some cousins argue. Others disagree and argue that some of the land could be sold and the remainder protected through easements held by the Pee Dee Land Trust.

In my urban life as the co-director of City Lore, working closely with co-director Molly Garfinkel, who runs our Place Matters Program, we engage time and again with conflicts between market values and the human values of community and place. This past year, one of our favorite restaurants, Bessou, with its unique modern take on Japanese comfort food, was priced out of its spot on the Lower East Side’s Bleecker Street, leaving our mouths forever watering for the vanished umami flavors of dishes like “blistered green beans with shishito peppers” and “shisho cigars.”

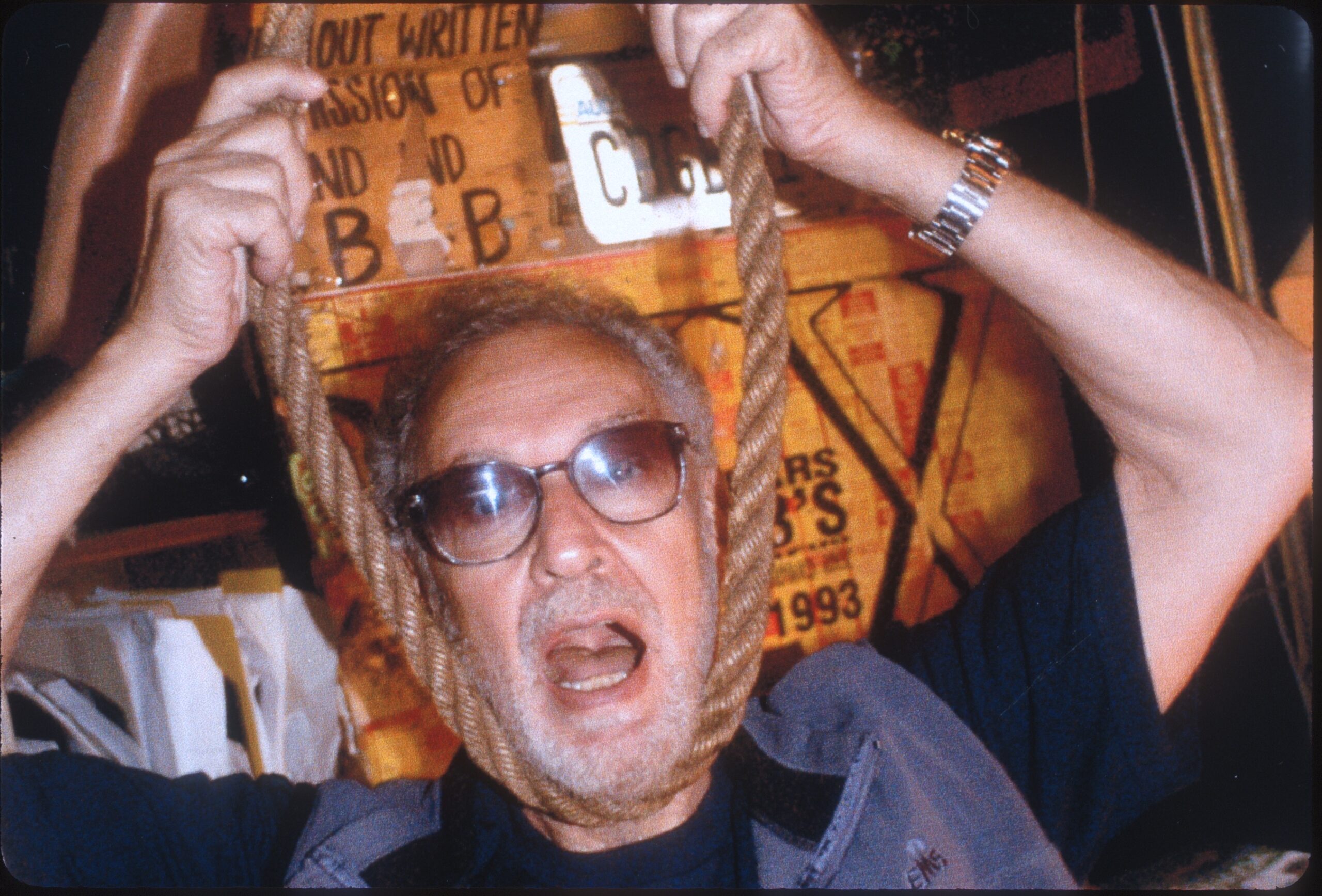

A few blocks away on New York’s Bowery, the building where CBGBs birthed punk rock, now houses John Varvatos fashions. Run by Hilly Krystal from 1973-2006, Blondie, the Ramones, and Patti Smith, along with hundreds of bands with names such as the Mumps, Mink de Ville and the Miamis screamed their hearts out at CBGB’s hole-in-the-wall stage. The club paraded its iconic appendages – piercings (often with safety pins), tattoos, mosh pits, and slamdancing. Despite its cultural and historical significance and City Lore’s and others’ activism to save it, CBGB’s closed in 2006 over a rent dispute. Similarly, years of history and generations of memories were not enough to keep Coney Island’s House Under the Roller Coaster or the Staten Island cottage owned by Dorothy Day, founder of the Catholic Worker movement and a candidate for sainthood, from being demolished, in 2000 and 2001 respectively.

A few blocks away on New York’s Bowery, the building where CBGBs birthed punk rock, now houses John Varvatos fashions. Run by Hilly Krystal from 1973-2006, Blondie, the Ramones, and Patti Smith, along with hundreds of bands with names such as the Mumps, Mink de Ville and the Miamis screamed their hearts out at CBGB’s hole-in-the-wall stage. The club paraded its iconic appendages – piercings (often with safety pins), tattoos, mosh pits, and slamdancing. Despite its cultural and historical significance and City Lore’s and others’ activism to save it, CBGB’s closed in 2006 over a rent dispute. Similarly, years of history and generations of memories were not enough to keep Coney Island’s House Under the Roller Coaster or the Staten Island cottage owned by Dorothy Day, founder of the Catholic Worker movement and a candidate for sainthood, from being demolished, in 2000 and 2001 respectively.

As preservationists, we sometimes speak metaphorically about “cultural capital” and “social currency.” But what if there were an actual currency of memory and meaning to prevent places with deep roots in a community to be sold or displaced. What if memories, associations, and values were transformed into units of meaningful exchange?

In 2008 – 2009, Bitcoins, an imagined cryptocurrency took the world by storm. Bitcoins have value because people agree they have value, and they function as currency. In that spirit, let’s imagine “Place Coins” to assess the human attachment to places.

Money is distributed unequally: some people are born into it; some steal it; others earn it. Some people have a knack for making money. And money makes money. Place Coins, units of emotional investment, on the other hand, would be dealt out equally, as in a game of Monopoly. Each successive year of life would be a bit like passing “Go” as players receive another equal allotment of Place Coins. These would correlate with the time, care, and emotional energy that human beings invest each year in the places they love. By setting down Place Coins on places, you cannot actually buy them; rather, you protect them from being bought or destroyed by others.

The U.S. dollar was once backed by the gold bullion held at Fort Knox. The Place Coins would be backed by and correlated with time and feeling. People would invest this new currency on the places where they spend their work and time. Historical sites with powerful memories and associations would yield a dividend in Place Coins, and, likewise, sites of ongoing use would earn Place Coins according to the value the community invests in them.

The formula for their value would be roughly this. The length of time in days spent in a place times the depth of feeling, care, and investment put into that place would determine its value in Place Coins. These then would be units of quality time measured by the length of days multiplied by the intensity, love, emotion, and joy put into given moments in a given place, doing justice to the way time is experienced. We both care about the place, and take care of it.

.Calculated in this way the 200+ years of community life along Pocket Road would take into account the two-room Back Swamp Schoolhouse, now an active community center; swimming holes on the “ holy water” of Black Creek where picnics and creek floats have been held for generations; the seasonal parties and celebrations including sweet corn parties in late summer, peanut boils in the fall, bird suppers in the winter, and fish fries in the spring when the herring run in the Pee Dee River, and the years invested and battles fought by the community to protect the rural nature of the land. Multiplying the 200+ years times the number of meaningful moments invested in those places easily comes to, playfully, say 15 or 20 million Place Coins, enough to protect the land from development even from a 10 million dollar offer.

CBGB’s democratic stage also accumulated a fortune in our new currency. When Joey Ramone died in 2001, memorials cropped up spontaneously outside of CBGB’s, then sprawled across the sidewalk for months. The club is emblazoned in the bacchanalian memories of hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers. Listening to the Ramones sing “I Want To Be Sedated” or “Sheena Is a Punk Rocker” for the first time offered the intensity ordinary life does not provide. Those moments soaked into the worn wooden walls like the layers of flyers and stickers that marked the club’s historic interior; the club, in turn, came to symbolize the exalted moments in the lives of the rockers, punkers, ravers and vamps who shared the experience. CBGBs had accumulated a wealth in Place Coins from its historical associations with Patti Smith, Sonic Youth, and the Ramones, as well as from their ongoing use by generations of rebellious youth. CBGB’s closed in 2006, thrown out over a disputed $76,000 in back rent and a threatened $20,000 a month rent increase. If their Place Coins had been calculated and brought to bear, they would have easily covered those costs and more. CBGBs could never have been evicted without their consent.

Although Place Coins are not likely to be minted and adopted as an alternate currency, we need to find a method of measuring public attachments in our collective decision-making about the value of place. We need forms of cultural capital that are as quantifiable and real as money, which, after all, have only an agreed-upon value. Sure, arguing the value of the local is difficult, even costly. But trying to recreate a community after it has been turned into chain stores or high-end clothing shops is not possible at any price. Calculating the value of sites like the Back Swamp community on Pocket Road that includes the Ervin-Dargan cousins, multiplying the years times the emotional investment, may yield to an assessment of value so vast that certain properties become invaluable. Not available at any price.

As of this writing, the story of the development on Pocket Road has a happy ending. The community wrote letters and lobbied the Florence County Council to keep the land zoned as agricultural, bringing to the fore the reduced quality of life that further development would bring as well as the importance of preserving rural land and communities. The Back Swamp Community activists invited members of the Florence County Council to hold a hearing at the Old School House where community members spoke about their love for and years of fighting to protect their community. The developer pulled out. Community pressure may have helped but, of course, the land is still for sale. The accumulation of Place Coins prevailed.

For now.

5 thoughts on “Place Coins: Contemplating an Alternate Currency for the Value of Place”

Delighted to have posts from this site.

Steve- share this with Historic Preservation folks- they are paying more attention to the issues you raise in this essay and they actually have the power (Sometimes!) to impact decisions about places

Love this Steve! Worth thinking about designing the possibility of currency flows with this idea. Perhaps a currency that could be earned through an economy of care/participation for people, and in logging experiences with places, another value creation process for the accumulation of value of that place…

Hi Steve

I read every word of your blog post. Somehow we were sentences just carry you along, quietly, building to finale, which is really a beginning. I love your place idea!

Fascinating, but I honestly do not at all understand how Place Coins would translate into real, actual money that could assist or save any given site, such as CBGB. Love to hear more because I still don’t get it! 🙁