Poetry of Everyday Life Blogpost #5

June 15, 2017

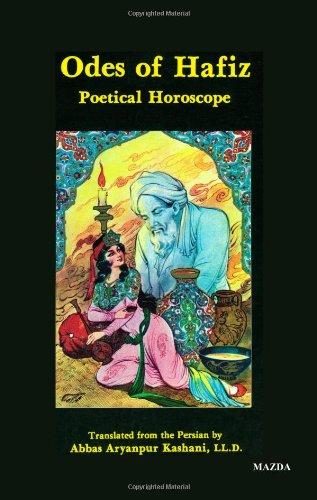

In a bedroom she shared with her three siblings in Elmhurst, Queens, 9-year-old Sahar Muradi snuggles up to her mom. Sensing her daughter feeling pensive, her mother asks, “Is there something on your mind?” Then her mom reaches for the magical red book. Sahar remembers, “I can picture it – the book was leather-bound, frayed from overuse. It was small and fit perfectly into my little hands.” This was Hafez’s divan, the collected works of a 14th century revered poet from Iran, where great poets are considered seers. Hafez’s sobriquet or nickname is lesān-al-ḡayb, or The Tongue of the Unseen.

“My mother received her book from my grandfather (my dad’s dad),” Sahar wrote to me. “My grandfather had bought it while visiting family in Mashad, Iran, and he eventually brought it with him to NY. My grandfather left Kabul for NY before we did (my dad came in 1981, shortly after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and Mom and we kids came in 1982). He gave us the book when we arrived. As new immigrants, he probably knew we’d need all manners of guidance.

“My mother had taught us to turn to Hafez’s divan with a harrowing decision or a life impasse (apparently, she had even consulted him on whether to marry my father!). With the book in my hand, I would start the ritual by reciting aloud in Farsi the invocation one makes prior to posing their burning question:

Ya Hafez-e-Shiraz

Tura ba shakh-e nabat-et qasam meytum

Agar ras-e-ta ba ma bogoye bareh azee

Oh, Hafez from Shiraz

I ask you to swear on your branch of sugarcane [i.e. your beloved]

That you will tell me the truth about the following

“I would hold the question silently in my heart. To tell your question aloud would surely jinx it. And to tell your mother your question – well, that would be self-sabotage! My secret was with Hafez, immune from any parental judgment. Then I would open the book at random and hand it over to my mom to read the Farsi. Oddly, she wouldn’t read the poem on the page it fell on – she would read the preceding one as if reading the obvious one wasn’t chance enough.”

She then would interpret the poem for an answer to my tortured question. As I grew, I often asked silly questions – ‘Does so and so like me?’ ‘Is this popular girl going to be my friend?’ and, later, ‘Will I get into the university?’ ‘Will my father’s health improve?’ My mom would offer her interpretation of the poem, and she usually made it sound as if some good would come of it. I would sometimes try to manipulate the outcome. I would test to see if the ‘best’ poems, the ones with the most affirming answers, were more in the middle of the book or towards the front or the back. Of course, that never worked.”

“Turning to Hafez was a family thing we did, although my mother was the guardian of the divination. It was part of the way we bonded (and continue to). Because of our reverence for him, we’ve even done family translations of Hafez’s poems. This is one we love:

What is better than pleasure, conversation, a garden, and spring?

Where is the cup-bearer? Tell me, why are we waiting?

Seize every joy that reaches your hand.

What anyway is the end of all our efforts?

Fathom: we are tied to life by a hair. Think twice.

Be kind to yourself; what do the little griefs matter?

~translated by Ali, Shaima, and Sahar Muradi

“During my childhood, my father did not engage in the tradition as much as my mom did. He would really only turn to it if something bad happened or he couldn’t make a decision on his own. But my mom says that in the last year or so of his cancer, before he passed away last October, he would turn to Hafez after morning prayer.”

Fal-e Hafez is the name of this ancient tradition in which a reader asks Hafez for advice, often when facing a difficulty or an important juncture in life. People open Hafez’s divan the way they might consult an oracle, with a deep wish for a soul requesting guidance. This custom was so well known that even Queen Victoria was said to have consulted Hafez in times of need.

Why Hafez? Hafez is known for his lyrical dexterity and his philosophical musings, for calling out moral hypocrites and for elevating social outcasts. Hafez describes himself in one poem “with hair disheveled, face flushed, and smiling drunkenly / Wine cup in hand, shirt open, singing poetry” (translated by Jawid Mojaddedi). He sings the song of the sinners and sees the beloved in their wine cups. One poem:

When Hafez’s coffin comes by, it’ll be all right to follow behind.

Although he is a captive of sin, he is on his way to the Garden.

~translated by Robert Bly and Leonard Lewisohn

“He is the Persian Leonard Cohen,” Sahar said. He is perhaps a patron saint of sinners and I was reminded of Cohen’s line, “There is a crack in everything / That’s how the light gets in.”

Fal-e Hafez is part of a larger tradition of bibliomancy—using books for divination—found in many cultures and religions. Christians often open the Bible in the same way, as my friend Ruth Campo pointed out to me. “Did you do that when you were a kid?” I asked her. “No,” she answered. “Only as an adult. Back then I thought I knew all the answers.”

Hafez died in 1390 and for more than 600 years Persians, Middle Easterners, and lovers of Sufi poetry have turned to his poems for advice. The tradition persisted through times of war, despots, torture, love and death through the centuries. Certainly today the political and personal situations have changed, to say nothing of the technologies. So whether the issues came up in the 14th or 19th or 21st century, the answers come in the form of a poem. Why a poem? Perhaps while the options being considered in the question may be simple, they may require an answer deeper than a yes or no because our lives are not so clear-cut.

“Unless your mother is doing it for you,” Sahar told me, “you are interpreting for yourself. Hafez is the intermediary, if you will; you draw your own conclusions and find the meaning in the poem that serves as a useful metaphor for your life.” The poem connects divergences and gaps with metaphor. Then the poem, in turn, becomes a metaphor for your life, encouraging you to think poetically and philosophically about decisions in your life. In the end, you find your own solution. As Jackson Browne sings, “bring your own redemption when you come.”

So how can we use this ancient tradition to survive these troubled times? A question that many of us have in our hearts is, “how do I survive the Trump administration?” If I were to pick a work of contemporary poetry to open at random for this question, I would probably select the Collected Works of William Butler Yeats. (Of course, telling you the question would probably jinx it.) And when I open the book like cutting a deck of cards, I feel sure the page would fall on Yeats’ “Second Coming”

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Or perhaps we would do better to consult Hafez, and not only because he calls out hypocrites. “My poems,” he writes, “lift the corners of the mouth – the soul’s mouth, the heart’s mouth. And can effect any opening that can make love.” Since now it is possible to experience the Fale-e Hafez online, I decided to pose my not-so-secret question at https://www.hafizonlove.com/fal.htm. Here is a verse from Ghazal 327 that the webmaster of randomness found for me:

Tending to desires of the heart

Privately I make a start

Let the liar’s venom part

And let friends play their role

~translated by Shahriar Shahriari

The poet, unlike the politician, always tells the truth, at least a truth. Perhaps the tradition of the Fal-e Hafez is a way to seek wisdom in poetry rather than politics and to find our own pathway and meaningful ways to engage with the world. “At times like this,” Sahar told me, “when so much appears corrupt, the clarity of a poem can seem sacred.”