Poetry of Everyday Life

Blogpost #16

by Martha Dahlen

intro by Amy Chin and Steve Zeitlin

As the Year of the Pig cycles into the Year of the Rat in the Chinese zodiac, the writer Martha Dahlen gives us a primer on the many meanings of auspicious New Year greetings to ensure our City Lore family enjoys a happy, harmonious and prosperous year.

–Amy Chin, City Lore Board Member

Walking through the twisty streets of Chinatown a few days before the big New Year celebration to take place January 25th, I was intrigued by the ubiquitous red paper signs and greetings. My friend, Martha Dahlen, who lived for 20 years in Hong Kong, explained to me that these are decorations, but decorations with significant meanings. They are part and parcel of the poetry of everyday life for many Chinese people, especially Cantonese, in China, Hong Kong, and New York. Here is her take on it.

Walking through the twisty streets of Chinatown a few days before the big New Year celebration to take place January 25th, I was intrigued by the ubiquitous red paper signs and greetings. My friend, Martha Dahlen, who lived for 20 years in Hong Kong, explained to me that these are decorations, but decorations with significant meanings. They are part and parcel of the poetry of everyday life for many Chinese people, especially Cantonese, in China, Hong Kong, and New York. Here is her take on it.

The Chinese New Year, or Spring Festival, is by far the most significant, most widely celebrated holiday in China. The belief is strong that how you begin the year will influence your fortune throughout the coming months. Hence, as New Year’s day approaches, people pay off debts, clean house, buy new clothes, prepare gifts, cook auspicious foods, decorate with blooming flowers and fresh fruit (especially round, golden citrus), and hang red banners proclaiming confidence that the coming months will be prosperous and joyful. When they meet, people exchange greetings but, in addition to the generic “Happy New Year!”, there are many other, more colorful phrases expressing specific aspirations. Further, the Chinese believe each New Year has its own dynamic energy–something like a new weather system coming in–as represented by the Animals of the Chinese Zodiac. Thus, the New Year offers the chance for a fresh start on several levels, and the variety of Chinese New Year phrases captures the range of this opportunity.

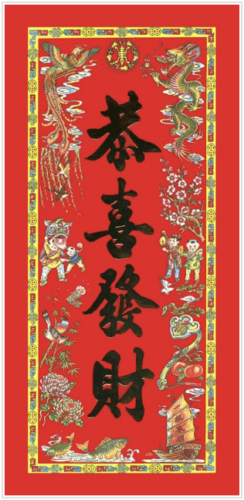

The New Year greeting most familiar to non-Chinese people is probably Gung Hei Fat Choy, which is the Cantonese pronunciation of the characters which, in Mandarin, are pronounced as Gong Xi Fa Cai. Gong Xi (Gung Hei) is a two-word combo that means “Congratulations!” with overtones of respect, sheer happiness, and blessings. Fa (Fat) means to grow, increase (the same word is used to refer to yeasted bread dough). Cai (Choy) refers to money or wealth.

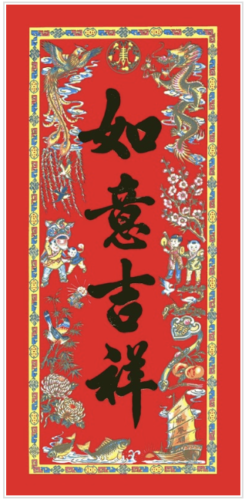

For Hong Kong Cantonese, the phrase is an exuberant affirmation that life is good, something like, “Congratulations on winning the lottery!” For other Chinese, the phrase seems crass, and they prefer expressions, such as Ji Xiang Ru Yi. Ji Xiang means “auspicious”, while Ru Yi means “as wished” or “comparable to your intentions”. The whole phrase is loosely equivalent to, “May all your wishes come true.”

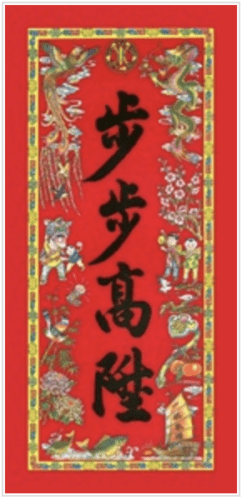

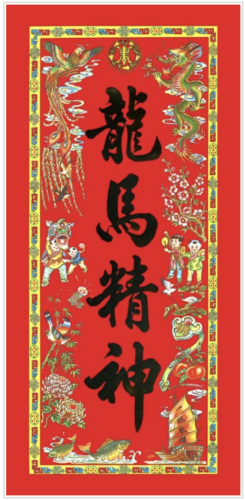

There are age-appropriate phrases. For example, let us say you meet your young nieces or nephews; you might greet them with, Bu Bu Gao Bi (step-step-ascending-throne”), hoping to inspire them to greater efforts in school. To the entrepreneur in your family, you might say Wan Shi Sheng Yi (ten thousand-things- victory/success) or Long Ma Jing Shen (dragon-horse -vitality-power). In the latter phrase, the dragon symbolizes heavenly greatness, while the horse represents earthly power, and the whole can be loosely translated as, “Fly high! Charge ahead!”

There are age-appropriate phrases. For example, let us say you meet your young nieces or nephews; you might greet them with, Bu Bu Gao Bi (step-step-ascending-throne”), hoping to inspire them to greater efforts in school. To the entrepreneur in your family, you might say Wan Shi Sheng Yi (ten thousand-things- victory/success) or Long Ma Jing Shen (dragon-horse -vitality-power). In the latter phrase, the dragon symbolizes heavenly greatness, while the horse represents earthly power, and the whole can be loosely translated as, “Fly high! Charge ahead!”

For people experiencing the challenges of aging, you could greet them with a fervent Shen Ti Jian Kang (body-strong and healthy) or the poetic Shou Ru Song Bai (longevity-like –pine-cypress), as both pine and cypress trees are classic symbols of long life with dignity. (Note: Both these phrases are also appropriate birthday greetings.)

By this time, you may have noticed that all of these phrases are four characters; in fact, they may be a subset of the huge group of Chinese aphorisms known as cheng yu. These are pithy statements that express, in meaning, Chinese culture, and in form, Chinese language. For example, each Chinese character, in every dialect, is pronounced as a single syllable. Thus, four words have a fixed, regular rhythm. Every dialect (the most common being Mandarin and Cantonese) are tonal, so each character has a certain pitch and phrasing. In other words, a four-word phrase has both rhythm and melody, making them easy to memorize and recite. Indeed, some families, gathering at Chinese New Year, will compete among themselves to see who can remember more of these colorful expressions, in a kind of musical poetry contest.

Another aspect of the Chinese language at play here is the fact that the number of characters in the language far outstrips the number of ways monosyllables can be pronounced. The result is that characters differing radically in meaning may be pronounced similarly or even the same. Linking two characters–in a sense, creating two-syllable words—is one way to avoid confusion in speaking. For example, the word, Ji, when spoken could refer to the various characters for good, a thorn bush, or the great ultimate (as in Tai Ji). Similarly, Xiang could mean auspicious, or details/minutia. But Ji Xiang, the two together, immediately narrows the field, such that the listener automatically hears the intended meaning (good fortune).

Another aspect of the Chinese language at play here is the fact that the number of characters in the language far outstrips the number of ways monosyllables can be pronounced. The result is that characters differing radically in meaning may be pronounced similarly or even the same. Linking two characters–in a sense, creating two-syllable words—is one way to avoid confusion in speaking. For example, the word, Ji, when spoken could refer to the various characters for good, a thorn bush, or the great ultimate (as in Tai Ji). Similarly, Xiang could mean auspicious, or details/minutia. But Ji Xiang, the two together, immediately narrows the field, such that the listener automatically hears the intended meaning (good fortune).

Several such pairs occur in multiple phrases; e.g., fu gui (honorable), da ji (big luck). Ping An, meaning “peace and safety” is another such unit. So, for example, putting the phrase Chu Ru Ping An above your door confers peace and safety (ping an) on all who leave (chu) and enter (ru). There is also Si Ji Ping An, meaning “four (si) seasons (ji), peace and safety”. And Lao XIao Ping An, meaning “old (lao)-young (xiao)- peace and safety” (Lao Xiao Ping An is also the name of a steamed beancurd and fish dish, suitable for those two groups who might lack teeth).

Another characteristic of these phrases is the lack of grammatical nuances. No little words tell you how the ideas represented are meant to be linked. For example, Kai Gung Da Ji is translated, word by word, as “Start-work-big-luck”. Does that mean IF you start work or WHEN you start work you will be lucky? Does it promise luck (or blessing) AFTER working? No matter: the listener simply understands that work and good fortune are linked. Furthermore, with no verb tense, these phrases fall squarely in the category of affirmations: each depicts a condition as though it already exists.

Home and family are important themes in greetings as they are in Chinese culture. For example, Man Tang Fu Gui (Full – meeting hall –wealth –honorable.) The second character, ‘tang’, suggests the central courtyard of a Chinese extended family. Thus the phrase seeks to capture the deep glow of contentment, pride and honor one feels when beloved children and grandchildren gather at home with their parents. Speaking of parents, one phrase that mothers love to use, and newlywed children are loathe to hear, is Jin Yu Man Tang, which literally means gold (jin) and jade (yu) fill the home, and figuratively means “I am looking forward to grandchildren any time now”. Abundance is a major theme. So we have Nian Nian You Yu (year-year-have-surplus). As the word for surplus sounds like the word for fish, a whole fish is traditionally served at every New Year’s eve dinner–and it is important that some fish be left, symbolic of surplus in the coming year. Reportedly, in earlier times, during lean years, a farmer might serve a wooden fish to ensure that it would be leftover, thereby also ensuring surplus in the coming year.

Home and family are important themes in greetings as they are in Chinese culture. For example, Man Tang Fu Gui (Full – meeting hall –wealth –honorable.) The second character, ‘tang’, suggests the central courtyard of a Chinese extended family. Thus the phrase seeks to capture the deep glow of contentment, pride and honor one feels when beloved children and grandchildren gather at home with their parents. Speaking of parents, one phrase that mothers love to use, and newlywed children are loathe to hear, is Jin Yu Man Tang, which literally means gold (jin) and jade (yu) fill the home, and figuratively means “I am looking forward to grandchildren any time now”. Abundance is a major theme. So we have Nian Nian You Yu (year-year-have-surplus). As the word for surplus sounds like the word for fish, a whole fish is traditionally served at every New Year’s eve dinner–and it is important that some fish be left, symbolic of surplus in the coming year. Reportedly, in earlier times, during lean years, a farmer might serve a wooden fish to ensure that it would be leftover, thereby also ensuring surplus in the coming year.

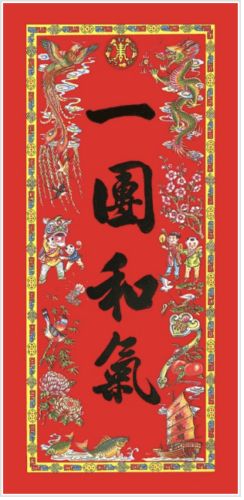

Many of these greetings are codified in rectangular red banners known as fai chun (Cantonese pronunciation, as they are predominantly a Cantonese tradition). These can be seen throughout the year in homes, offices, businesses and restaurants, but are especially prevalent during the New Year season. Most people buy their fai chun, but it is generally agreed that writing them yourself will give them more power.

Fai chun make aspirations public and permanent. Currently in Hong Kong, people are using this traditional form to express their political, as well as their personal, hopes for the coming year. However, the former is not without risk. “Satirical” decorations are banned, and people worry about surveillance. One clever fai chun is a square writing of a traditional four character phrase zhao cai jin bao (finding-wealth-advancing toward- treasure/gems). When viewed upside down and twisted just a little (the many parts of a Chinese word make this possible), it becomes zhui qiu zi you min zhu (stubbornly pursuing-freedom- democracy). Such writing is even more clever because the words for “upside down” in Chinese (dao li) sound like the words for “already arrived” (dao le). So posting this one upside down not only makes it look innocuous but also increases its power.

As January 25 approaches, prepare to Ying Chun Jie Fu (Welcome spring [as] luck enters) with the fervent hope for Tin Ha Ping An(heaven-earth, peace and safety). Say it, believe it, live it. Fu Lu Shou Quan: All blessings are yours.

1 thought on “Everything You Ever Wanted Is Coming True: Chinese New Year’s Greetings”

This was terrific. Many thanks. I’ve been studying, qigong and tai chi, in Chinatown with a Chinese group, mostly Cantonese. Their English is either non- existent or not adequate to relay all this wonderful information. I’m delighted!

San nin fai lok!