Svetlana Alexievich’s Secondhand Time Holds Truths for Soviet Russia—and the US

A Review and Reflections

Poetry of Everyday Life Blogpost #26

Produced in collaboration with Voices: Journal of New York Folklore

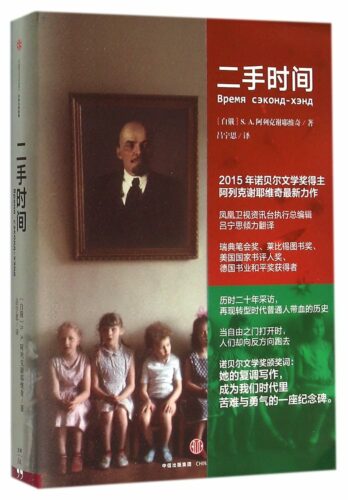

I always underline my books. I read with a pen in hand, and all the books I read have a few striking passages underlined – which is precisely why I don’t borrow books from the library. My now-worn copy of Svetlana Alexievich’s 2013 masterpiece Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets, in translation by Bela Shayevich, has multiple passages underlined on every page. Comprised of individual, intimate, and extensive monologues interleaved with a collage of other voices, the book is the most powerful collection of oral histories I’ve read. As Philip Gourevitch writes, “She shapes her investigations of Soviet and post-Soviet life and death into epic dramatic chronicles as universally essential as Greek tragedies.”[1]

In her book, Svetlana speaks of finding a “guide,” a narrator or interlocutor “who leads me on my travels through people’s worlds.[2] She selects her subjects carefully, often those with dramatic, tragic experiences, and revisits them repeatedly to present monologues extending over twenty or thirty pages. As Maria Voiteshonok, a 57 year-old writer tells her, “So many times, I’ve wanted to tell someone all of it. To speak my fill. But no one has ever wanted to know: “And then what…and then what?”[3] Svetlana listens with her heart, and those she listens to, pour their hearts out.

For the past four years, the poet Bob Holman and I have been doing our share of listening for a project called Across the Great Divide. We created this as a multi-pronged initiative to build cultural understanding across this nation’s political schisms through storytelling and heart-felt, simple “Where I’m From” poems. Through homegrown poetry brought to life on screens, pages, and conversations, the initiative seeks to bring out the individuality and common humanity of Americans from different political orientations, ages, genders, and cultural backgrounds from every part of the country. We take the stance that this nation is not made up not of reds and blues (or even pinks and purples), but of 300 million political family trees – 300 million people, with many nuanced beliefs and political family trees. In an interview about this project for the National Poetry Foundation’s podcast, Helena de Groot suggested that, given the nature of our project, we might wish to read Secondhand Time. We did – it rocked our world and changed the way we thought about our work.

Svetlana was motivated by some of the same impulses that drive us. One of those impulses is the desire to truly hear all sides, all perspectives of the story. Bob and I are both liberals; thus, the challenge in creating Across the Great Divide for us is to engage with conservatives. Svetlana is a leader of the Belarusian democratic movement, a dissident, now living in Berlin. For her, the challenge was to engage with her past and the ideals of communism that eventually led to Putin. In September 2020, Alexievich alerted the press that men in black masks were trying to enter her apartment in central Minsk, and that all of her compatriots were in prison or in exile.[4] When Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, a news report noted that she could not stop crying. “My mother is Ukrainian and my father is Belarusian,” she said in an interview with The Asahi Shimbum. “I truly love Russia and grew up within its culture. I absolutely could not believe that a war would begin.”[5] She described what unfolded in Ukraine in 2022 as “savage beasts crawling out of human beings.”[6]

Yet she writes with enormous compassion about the Soviet experiment with communism, and its collapse during the Gorbachev years. She begins her book, “We’re paying our respects to the Soviet era.”[7] As one of her subjects, Elena Yurievna, tells her,

I was born Soviet… My grandmother didn’t believe in God, but she did believe in communism. Until his dying day, my father waited for socialism to return…[8] I love the word “comrade”, and I’ll never stop using it, it’s a good word…. Remember the Soviet place names – Metallurgists Avenue, Enthusiasts Avenue, Factory Street, Proletarian Street .. The little man was the most important one around…. Where are you going to see a Metro station devoted to dairymaids, lathe operators, or engine drivers today? [9]

Another subject, Margarita Pogrebitskaya, a 57 year old doctor, remembers the day she was accepted into The Young Pioneers. She lept up and immediately stood at attention on her bed. Her favorite holiday as a girl was November 7, commemorating the revolution of 1917. Her father took her to Red Square. She remembers the Spasskaya Tower clock that she believed the whole world set its time to. There was red everywhere, her favorite color – “the color of the revolution and of the blood spilled in its name.”[12]

Beginning in 1985, when Mikhail Gorbachev became the General Secretary of the Community Party, the reforms of Perestroika began. For Americans, Russia had been dubbed by Reagan the “evil empire,” and the dire threat of nuclear war hung over both countries. They had been looking at one another “through the crosshairs.” In 1989, the Berlin Wall fell, and the Soviet Union dissolved into separate nations. No one in her book recognizes that many of those nations desired their independence.

But the demise of the USSR was seen as a tragedy to the true Soviets. “Our parents sold out a great country for jeans, Marlboros, and chewing gum…” says one interviewee. “We dreamed of having a McDonald’s with hot hamburgers, we wanted everyone to be able to buy themselves a Mercedes, a plastic VCR. We want pornos in the kiosks.”[17] “The first thing to go was friendship…. Suddenly everyone was too busy, they had to go out and make money.”[18] Elena Yurievna, a secretary of the district party committee adds: “…Not everyone is capable of stopping at nothing to tear a piece of the pie out of somebody else’s mouth.”[19]

The nostalgia for Soviet communism echoes Donald Trump’s Make America Great Again slogan and campaign. Both imagine a golden age which may never have existed except in the memories of nostalgic elders and a privileged few. Many of the protagonists in Secondhand Time might as well be saying “Make Russia Soviet Again.”[20] Both Americans and Russians nostalgic for the old days forget, perhaps, that one reason those old days look so good is, as one person put, “we were young then.”

For those of us working on Across the Great Divide, Svetlana’s book led us to understand our own project with greater clarity and depth. We recognized in her book that there is more than one Divide. We now think about our initiative as Across the Great Divides. In Trump’s MAGA movement, believers hearken back to days of imagined prosperity. Russian nostalgia is quite different. As Svetlana notes in her Nobel speech, “Russians don’t really want to be rich, they’re even afraid of it. What does a Russian want? Just one thing: for no one else to get rich.”[21]

At the same time, Svetlana’s masterpiece takes us beyond these great divides into the very heart of what it means to be human, to the soul-fullness of being. “I’m interested in the history of the soul,” she writes in her Nobel acceptance speech. “The everyday life of the soul, the things that the big picture of history usually omits, or disdains.”[23] Her characters philosophize. “After Oleysa’s death,” says her mother, Ms. Nikolayeva, “I found an old notebook of hers from school, it has an essay in it called ‘What Is Life?’” Her daughter writes, “I want to describe the ideal mankind should strive for… The purpose of life is whatever makes you rise above….”[24]

Svetlana’s subjects philosophize on the deepest sides of life:

Spirit – The spirit is the spirit and everything else is just dirt. [25] (Alexander Porfirievich Sharpilo, 63 years old)

Death – Well, death never comes for no reason… death will find a reason.[26] (Marina Tikhonovna Isaichik)

Love – “I am filled with horror when I consider how hard you have to work to keep someone in your life. It’s like breaking rocks at a quarry! You have to forget about yourself, reject yourself, liberate yourself from yourself. There is no freedom in love… Loneliness is a kind of happiness.”[27] (Alisa Z. advertising manager, 35 years old.)

Memory – “My memory grows weaker, but my soul has not forgotten a thing.”[28] (Anonymous commentator)

Beauty – Ksyusha Zolotova, a 22 year-old victim of a Chechen terrorist attack in Moscow is asked, “Why are you crying? You’re so beautiful and here you are weeping.’ She answers, ‘First of all, my beauty has never gotten me anywhere, and second of all, beauty betrays me, it doesn’t correspond with what’s going on inside me…”[29]

Melancholy – “Like the plague, melancholy descends on us all. You’re riding the train, looking out of the window, and there it is: sadness. Everything’s beautiful all around you, you can’t look away, but the tears are running down your face and you don’t know what to do with yourself. That Russian sorrow… Even someone who seems to have everything always wants more. That’s how people live. They try to endure it.[30] (Yuri, partner of Yelena Razduyeva, worker, 37 years old)

Secondhand Time comes closer to poetry and fiction than investigative journalism, and, for that reason, it has been roundly criticized by some critics.[31] Although Svetlana’s interviews are tape recorded, the narrative is full of ellipses, and the pieces appear to be edited extensively. She doesn’t make apparent whether she clears her edited, recorded monologues with their speakers. But the truth she speaks is profound. She shows us the very thing Bob Holman and I are striving for in Across the Great Divides: wherever we are, in time or place, if we dig deep enough into the human condition, we will find common ground – if we don’t kill each other first.

Notes

* Alexievich, chapter heading, Secondhand Time: the Last of the Soviets (New York: Random House: 2017) p. 142.

[1] Blurb for the English translation of Secondhand Time.

[2] Alexievich, p. 434

[3] Alexievich, p. 235

[4] Belarus: Nobel Laureate Alexievich visited by diplomats amid ‘harassment, BBC. (‘https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-54079337).

[5] Akira Nemoto, “Svetlana Alexievich: Literature can prevent humans from becoming savage beasts,” The Asahí Shímbun, January 25, 2023, (https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/14811082)

[6] Akira Nemoto.

[7] Alexievich, p. 3.

[8] Alexievich, p. 43.

[9] Alexievich, p. 91.

[10] Alexeivich, p. 146.

[11] Alexievich, pp. 157, 158.

[12] Alexievich, pp. 91.

[13] Svetlana Alexievich – Nobel Lecture. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize Outreach AB 2024. Sun. 12 May 2024. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/2015/alexievich/25408-svetlana-alexievich-nobel-lecture-english/. Translation: Jamey Gambrell

[14] Alexievich, p. 295

[15] Alexievich, p. 100

[16] Alexievich, p. 195

[17] Alexievich, p. 111.

[18] Alexievich, p. 100.

[19] Alexievich, p. 51

[20] See “Interesting Times: Svetlana Alexievich on the Dangers of a Great Idea,” Amelia Glaser and Teresa Kuruc, Los Angeles Review of Books, November 22, 2016.

[21] Svetlana Alexievich – Nobel Lecture. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize Outreach AB 2024. Sun. 12 May 2024. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/2015/alexievich/25408-svetlana-alexievich-nobel-lecture-english/. Translation: Jamey Gambrell

[22] Alexeivich, Nobel Lecture.

[23] Alexeivich, Nobel Lecture.

[24] Alexeivich, p. 419.

[25] Alexeivich, p. 79.

[26] Alexeivich, p. 78.

[27] Alexeivich, pp. 346, 349.

[28] Review: In ‘Secondhand Time,’ Voices From a Lost Russia by Dwight Garner, May 24, 2016.

[29] Alexeivich, p. 351

[31] For criticism of Secondhand Time see Sophie Pinkham, “Witness Tampering Nobel laureate Svetlana Alexievich crafts myths, not histories,”The New Republic, August 29, 2016.