Many times, as I’ve rattled through Secaucus and Newark on New Jersey Transit trains, nose pressed to the window, I’ve gazed with longing over the train trestle at the Meadowlands. The narrow, watery channels wending through tall grasses, the swooping shorebirds, the rusty bridges and radio towers piercing the sky, factory smokestacks belching smoke and flames, a twelve-lane turnpike teeming with drivers hell-bent on their destinations—and behind all that, the miragelike Manhattan skyline. How wonderful it would be, I always think, to paddle through that labyrinth of pathways and take in the sights and smells and sounds of nature commingled with industry, and to see my home city from the unique vantage of an urban wilderness just five miles from the spire of the Empire State Building.

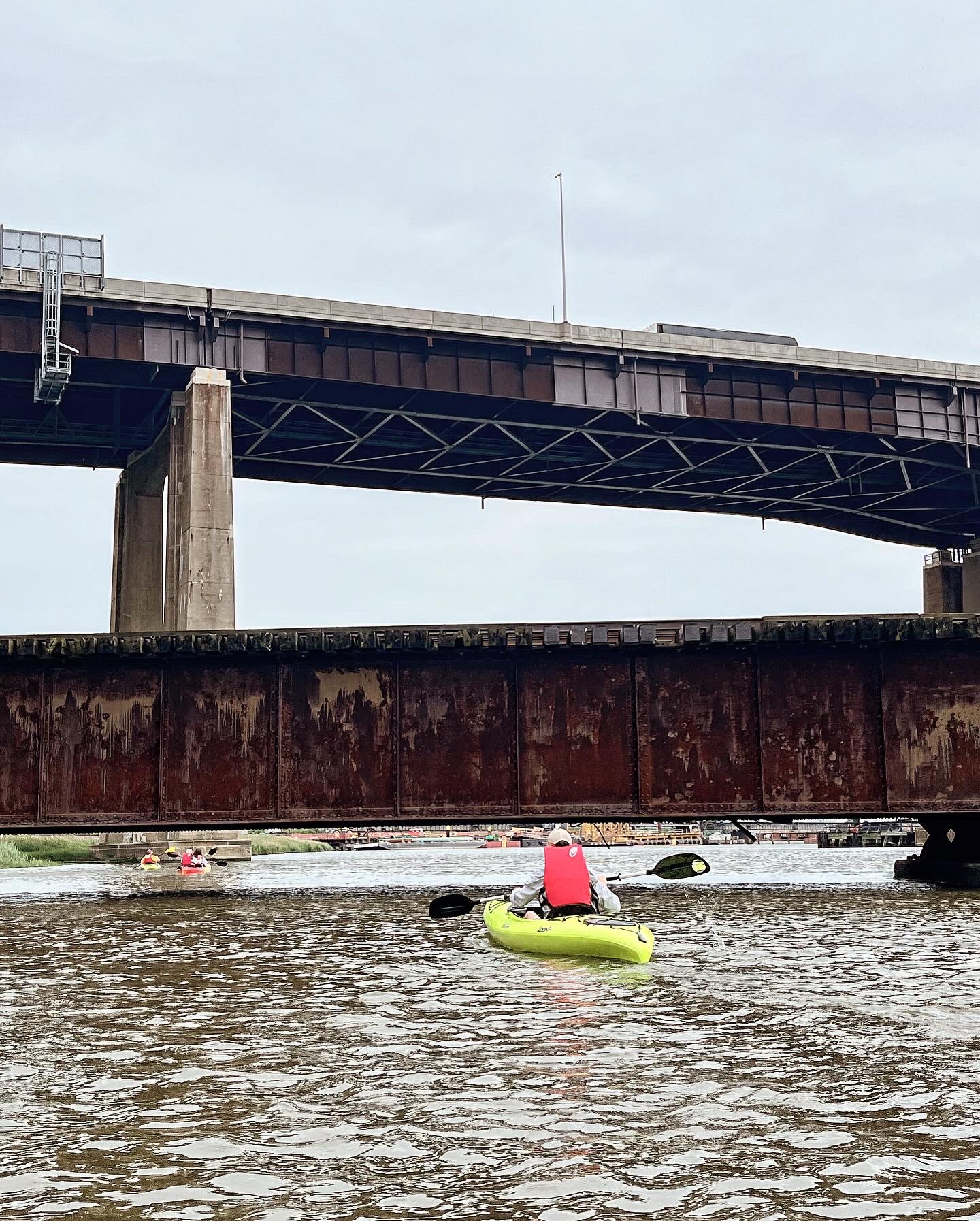

On a recent Sunday morning, I had the opportunity to do just this, thanks to the nonprofit Hackensack Riverkeeper, which hosts (among other events) guided kayak tours of the Sawmill Creek Wildlife Management Area in the tidal Hackensack River. The kayaks put in at Laurel Hill County Park and paddle out into a triangular section of the river framed by two spurs of the New Jersey Turnpike and the DB Draw, a derelict swinging rail bridge that has been left in the open position for river traffic like us.

As a light rain pricked the water, double-decker New Jersey Transit trains rattled over a railway bridge; blue Amazon trucks with smiling Prime arrows hummed past on the turnpike, blasting their air horns. Car carriers gave the illusion, from our perspective, that the top-level cars were themselves skimming along atop the trees. Planes from Newark International Airport droned overhead; the occasional seagull squawked. Because it was nearly high tide, our heads barely cleared the rusty beams of a trestle.

As a light rain pricked the water, double-decker New Jersey Transit trains rattled over a railway bridge; blue Amazon trucks with smiling Prime arrows hummed past on the turnpike, blasting their air horns. Car carriers gave the illusion, from our perspective, that the top-level cars were themselves skimming along atop the trees. Planes from Newark International Airport droned overhead; the occasional seagull squawked. Because it was nearly high tide, our heads barely cleared the rusty beams of a trestle.

According to Robert Sullivan, author of The Meadowlands (a John McPhee–esque tribute), the area was once a glacial lake that, as it receded, left a wake of rocks and debris, and as saltwater moved in, it became a swampy, boggy marsh, host to microorganisms and decomposing living matter. When humans began dumping poisonous waste from homes and factories, as well as military refuse from World War II, into the estuary, the Meadowlands became the largest garbage dump in the world. But the lower Hackensack River has recently been declared a Superfund site, and already conditions for the wildlife in the area have begun to improve.

A new rail bridge is being constructed, and we paddled right by it, commuter trains howling above us, and an American flag flying (puzzlingly at half mast) from a stalled crane. We also passed the infamous Snake Hill, a 150-foot igneous rock extrusion at a bend in the river. Snake Hill was once allegedly five times as wide and more than 200 feet tall, and home to an insane asylum, a penitentiary, and an almshouse. It has since been rebranded with the more mellifluous name Laurel Hill, but the reason for its local moniker, Graffiti Hill, was baldly evident, as was its legacy as the inspiration for Prudential Bank’s Rock of Gibraltar logo.

We passed concrete pylons tagged with graffiti, where two fisherman lolled. Our guides told us the brackish water is home to striped and largemouth bass, perch, northern pike, carp, and channel catfish, though we didn’t see any fish jumping on this cool, rainy day.

Finally we took a turn away from the bridges and pylons and, much as one would exit from a freeway, turned right onto a “road” through the grasses, and my dream of canoeing the paths of the Meadowlands was realized. As Sullivan points out in his book, “If you wander around in the Meadowlands for any amount of time, if you move from one unattractive attraction to the next, then you soon realize that outside of the swamp grass, the sky is the most predominant feature.”

Phragmites (pronounced “frag-MIGHT-ies,” our guides told us) and spartina (pronounced “SPAR-tina”) rose up on either side of us. The sussurration of the feathery seed heads and the stiff stalks of cord grass created the soundtrack I’d imagined from my sticky vinyl NJ Transit seat.

Just over the nose of my kayak I could see the Manhattan skyline, hazy in the distance. Looked at directly from the west, the Empire State Building and World Trade Center appeared much farther apart than they do from the common viewpoints around the city.

As we wended our way through the labyrinth of pathways, we heard the buzzy trills and gurgles of marsh wrens, which were so small we couldn’t see them; we just sensed a shifting in the grass. Red-winged blackbirds chack-chack-chacked. Cormorants, gliding just above the water’s surface, grunted and clucked. A heron took flight with its heavy, clunky wings and graceful neck outstretched, and we saw an egret perched on the edge of one of the marshy islands. The Meadowlands didn’t smell as foul as I’d anticipated: more a boggy smell of mud than of refuse. Our paddles struck the occasional plastic bottle or straw, or burst a rainbow shimmer of surface oil, but overall the water appeared fairly clean.

Ospreys had built nests on platforms in the marsh, and as we paddled by, the males protectively circled the nesting females in wide arcs. The giant nests on their poles at times seemed to blend in with the electricity pylons and radio towers and hulking relics of former industries.

We also passed factories, office buildings with mysterious logos, and even condos with balconies overlooking the Meadowlands, including one, the circa-1980 Harmon Cove Towers, that seemed to rise right from the swamp.

One ancient railroad bridge had a beautiful palimpsest of paint layers that seemed to echo the color themes of the meadowlands: dusky blue skies, rust, streaks of green. Swallows nest in its murky rafters.

When we got back to shore, I decided to explore the outcropping of land that makes up Secaucus, which has dubbed itself “the Jewel of the Meadowlands.”

I passed the massive, state-of-the-art Goya factory—responsible for producing, among other things, six hundred boxes of rice mixes per minute—and the gargantuan USPS International and Bulk Mail Center. But to me, the jewel of the Meadowlands was the confluence of industry and nature, the wailing of the air horns and the calls of shorebirds, the rattle of trains and of spartina stalks, the waving of the shoregrass and American flags against the open sky.

Sense & the City is a monthly blog exploring the hidden corners of New York City. Each month’s post is devoted to one of the five senses. Receive daily sensory impressions via Instagram @senseandthecity.

Sense & the City is a monthly blog exploring the hidden corners of New York City. Each month’s post is devoted to one of the five senses. Receive daily sensory impressions via Instagram @senseandthecity.

2 thoughts on “SOUND: Kayaking through the New Jersey Meadowlands”

One of the best of Caitlin’s essays, even though, perhaps strictly “not-New-York” and perhaps Multi-Sensory, rather than Sound alone. But fascinating and very evocative. I enjoyed learning of this world, so close and so far; so beautiful and so ugly; so natural and so manufactured.

Thanks for taking me with you! I’ve kayaked for 35 years all up and down the East Coast and most enjoy marshes — whether on Maryland’s eastern shore or around Baltimore’s gritty waterfront. And Sullivan’s “Meadowlands” is a keeper on my bookshelves.