The Poetry of Everyday Life, Blog Post #3

In October 2016, at the meetings of the American Folklore Society in Miami, I ran into Wolfgang Mieder, a professor of German and Folklore at the University of Vermont and the world’s leading expert on proverbs. He mentioned to me, as we shook our heads over the forthcoming election, that both candidates failed to take advantage of metaphors and colorful language in their campaigns. “Hillary Clinton,” he noted, “makes far more use of proverbs and metaphors in her books (It Takes a Village) than in her speeches.” He lamented that when she was asked about Obamacare, for instance, she didn’t have the proverbial sense to say, “Let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater.” “On the other hand,” he said, “Donald Trump really does appear to speak basically without metaphors or proverbial phrases.” Many great presidents, he pointed out, have provided the populace with enduring metaphors (Lincoln’s “A house divided against itself can not stand”) as well as proverbs and turns of phrase (Theodore Roosevelt’s “Speak softly and carry a big stick”).

So what are we to make of an artless president, a president with little or no feeling for poetry, language, or art? Metaphors connect ideas—and sometimes people—through language. We find we need poetry at occasions like weddings, where words can create union, funerals, where they ease separation – and politics where they span divides. Instead of calling on language and poetry to connect, Trump instead traffics in power relations. Power is hierarchical, a vertical line that severs other patterns, connections, and meanings. Trump’s linguistic creativity has been limited to insults and name-calling—Pocahontas, Lyin’ Ted, Little Marco, Jeb “Low Energy” Bush.

The language a person uses reflects their worldview, so it should come as no surprise that Trump would propose the elimination of the National Endowment for the Arts, along with the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Institute of Museum and Library Services and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, cutting America’s most literate institutions off at the knees. Their elimination would be akin to the destruction of ancient monuments in that it would be difficult if not impossible to ever bring them back. Abolishing them eradicates not only a vast body of knowledge, but also the career-long efforts of smart, caring civil servants who have made the most of the relatively small resources allotted them in honing processes to best support the nation’s arts, heritage, history, and culture.

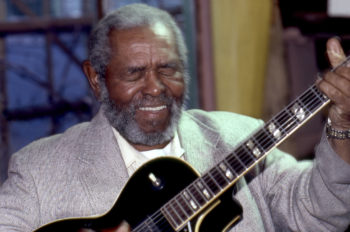

1982 National Heritage Fellow Brownie McGhee; photo by Tom Pich

In addition, our artists have been among America’s greatest ambassadors. Each year since 1982, for instance, nine to thirteen individuals from across the country are chosen to receive onetime National Heritage Fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, in recognition of lifetime achievement and artistic excellence. These individuals embody America’s heritage. The NEA has honored all variety of musicians and craftspeople, including blues singer Brownie McGhee, Irish fiddler Liz Carroll, Chinese opera star Qi Shu Fang, blues singer Mavis Staples, and Cajun fiddler Michael Doucet and Chilkat blanket weaver Clarissa Rizal. Cutting these agencies diminishes the significance of these awards and past awardees, including the parallel NEA awards in jazz and creative writing. I can imagine one of the former honorees saying someday, “Ah, yes, I once won an award from a government that cared about its culture and its art, but those agencies no longer exist.”

2006 National Heritage Award winner Mavis Staples. Photo by Tom Pich.

As Trump so emphatically noted, much of America, particularly in rural areas and small towns, is depressed and wants change. But the arts are part of the solution, not the problem. Shannon Monnat, assistant professor of rural sociology and demographics at Penn State University, explored the election data from districts where Trump did well in November. “I started looking at the data, especially within regions of the country where the opiod epidemic has received a lot of attention. And what I found was that Trump outperformed the previous Republican candidate Mitt Romney the most in counties with the highest drug, alcohol, and suicide mortality rates.” Funded arts programs were never a choice in many of these communities, and the National Endowment for the Arts can help bring a sense of purpose and alleviate some of the hopelessness that plagues these areas of the country, particularly if it were given the necessary resources.

“There’s nothing to do in this town but get high,” said a young woman from one of these towns in a recent television show.” A 2017 study published by the Social Impact of the Arts Project at the University of Pennsylvania notes that “cultural opportunities represent an important dimension of social inclusion and community well-being. The arts provide a resource that people can use to make sense of the world as it is and to imagine the future. Communities with a vital cultural life also enjoy a variety of ‘spillover effects,’ including stronger community and civic engagement, improvements in public health and social stability, and economic revitalization.”

A two-year ethnographic study of collaborative informal arts groups in the Chicago metropolitan area underlined the impact of arts on community. The study, led by Alaka Wali, looked at writing groups, painting circles, choirs, and other informal networks in which people congregate around a shared interest. They discovered that the collective pursuit of informal arts enables people to come together across the often-intransigent boundaries of race and ethnicity. The study suggests that these groups create a “metaphorical space of informality” with few barriers to participation, affirmation, and mentoring. The arts can help bring people together across the ethnic and social divides that defined the recent election.

2001 National Heritage Fellow Qi Shu Fang; photo by Tom Pich

“The only cure for life is art,” read a homemade sign that went up after September 11. A taxi driver in New York echoed this sentiment when I asked what he was listening to on the radio: “Music is only thing in this world that’s pure.” We need to pay attention to the poetry and art of everyday life to restore a sense of meaning and purpose to the mental health and well-being of communities across the American landscape.

Certainly, we can come up with our own colorful, metaphorical language to describe Trump in the Oval Office. We know that “there’s a bull in the china shop,” and that “the fox is in the henhouse now.” Trump’s words and actions also often bring to mind a Hasidic proverb: “Not only is what he says not true, but the opposite of what he says isn’t true either.”

Yet asking Trump to use more proverbs would certainly not solve the problem of arts funding or the value we place on arts as a nation; preserving the National Endowment for the Arts, on the other hand, is crucial to our civilization. It costs each American only the price of a postage stamp each year, but consider how much good its programs do in alleviating the despair and lack of opportunity that afflict so many communities across the nation—perhaps even in how many lives they save. It is said that when Winston Churchill, who always supported funding for arts and culture, was asked why he didn’t cut the national arts budget during World War II, he offered this fabled reply: “If we cut the arts, then what are we fighting for?”