Looking Back at the Corona Virus Ten Thousand Years from Now

by Kewulay Kamara

Poetry of Everyday Life

Blogpost #17

Intro

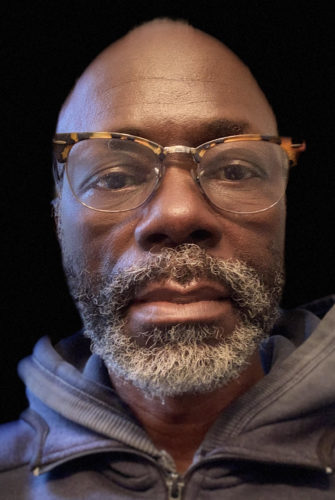

You don’t even know what you know till somebody asks,” my friend Kewulay Kamara told me. Born in the village of Dankawalie in northeast Sierra Leone, Kewulay Kamara is a member of the finah clan who serve as the oral poets and masters of ceremony for their communities. He immigrated to the U.S. at the age of 17 and, as an adult, he carries on the finah tradition as a storyteller and filmmaker with his new tools – the computer and the camera. Kewulay is also part of the futurist movement, working with UNESCO as a consultant and performer for their Taskforce on Foresight and Strategic Planning throughout the world. As a storyteller, Kewulay continually asks me get beyond whatever we’re going through to think about how we want things to be remembered. So who better to ask how this horrific era in our history might be remembered ten thousand years from now?

~Steve Zeitlin

In the spirit of the tradition that says: What is said is done and what is done is said, and of the persuasion that trusts that the infinite universe is created out of utterance, I want to tell the story today of COVID-19 as it will be told ten thousand (or even one million) years from now because, as Einstein foretold, chronological time is a fiction, and because what is said is done. I want to do this in the storytelling modality of the West African practice of libation. Let us stand on this earth 10,000 years from now, and pour a libation to honor the spirit of the ancestors who suffered through this pandemic. Let us begin by recounting events from way in the past and, at the same time, let us stand here today to project a future in the present. I will be there as I am here to witness today.

COVID-19 came at a time when the world had grown closer, when national borders seemed less important, and when the movement of people and things had begun to increase exponentially. The advent of COVID-19 had been predicted years in advance, yet its stealth, swiftness, and ferocity caused frantic course reversals: borders closed, neighbors masked, cities locked down, blocks blockaded, families separated, walls sprouting, and human immigration reversed like rivers flowing upstream. Everyone was advised to speak only with their mouth covered and their hands in their pockets; everyone was afraid even of their own lips.

The sages of the time sought to get a handle on The Mysterious Traveler. It was not human, it was not a plant, it was not animal, and it was not spirit; it was neither male nor female. No one actually claimed they’d seen it with the naked eye, but they understood that the naked eye does not know its enemy. It was known by its mark.

They saw the mark in one place first, but before the people could come to terms with it, the marks were spreading everywhere. Confusion and panic set in at the very foundations of power. Its path was mysterious—that is why some started calling it the Mysterious Traveler. The MT was like a hurricane that swept through cities and towns with abandon. It did not speak anyone’s language. It did not discriminate. It spared not the high and mighty royals, neither the holy people on the mountain, nor the prostitute in the street, the destitute in the gutter, the feeble in the wind, the humble on the earth, neither the young nor the old. The so-called “good” and the so-called “bad” met the same fate it its path—yet some could get out of its way more easily than others. As always, the working poor, the people of color, and the health care workers who could not get around its deadly approach, and stood firm in the face of it, paid the highest price.

The MT struck with a vengeance, killing over 100,000, including many of those who were brave enough to care for the sick. Many died difficult, ugly deaths, strapped to ventilators, and were so contagious that they died alone, with no one to hear their final gasp.

To some it appeared that the MT had come to turn every human folly and concern upside down. Before MT, humans had been fixated on economic growth, which translated into senseless movements directed by their priest, who uttered daily oracles from the stock markets. Every human value was subsumed under the assumption that what was good for the market was good for all. To service the market, forests were cleared, the wilderness decimated, the rivers dammed, and the oceans reduced to cesspools. It all made sense in their calculus, their primary method of reckoning good and bad.

With the MT came this headline:

Coronavirus: Mexicans demand a crackdown on Americans crossing the border.

It was a time when many predicted that a tide of African immigrants fleeing global warming would traverse deserts and meet a tragic demise baking in the sand under the sun, or that they would cross oceans, braving wild seas in flimsy traffickers’ boats, or face border dogs, armed guards, and razor wire fences on the other side of the Mediterranean Sea. The MT saw this reversed. During the reign of the MT came another headline:

African countries close their borders to European travelers, adventurers, a move that should have been considered 400 years before.

For the world of animals and plants, the MT was a superhero: it was the Liberator, the Avenger. Every animal in the bush, fish in the oceans, and tree in the forests was given breathing space as a consequence of the stay-at-home commands. As soon as humans started staying home, turtles reclaimed the beaches. Penguins danced. Fish in the oceans and trees in the forests were all given space to roam and to breathe. And homebound pets celebrated newfound time with their owners.

In Hong Kong a piece of graffiti read something like this: Kewulay Kamara with a blacksmith’s bellows (photo by Tom Pich)

Let us not go back to normal, because it turns out normal was a huge problem.

Before the Mysterious Traveler, the most rigorous arguments, the most courageous resistance, and the most fervent prayers couldn’t slow the traffic on the roadways, the seaways, or the skyward-belching factories, for the sake of reducing carbon emissions, to save the planet. The sun grew angry and joined forces with the rising oceans. The winds grew furious and spat fire as the earth grumbled. Yet for all their might, tornadoes and hurricanes only caused momentary discomforts. MT kept the cars parked and quickly smog began to clear. Human arrogance suggested that human beings had the power to determine their own destiny, as well as the destiny of the universe. Now it appeared to the wise that, ironically and tragically, in ways perhaps only the Gods can fathom, the survival of the species was aided by the Mysterious Traveler that killed so many. The earth had painfully and frighteningly been compelled to PAUSE!

During the PAUSE, people searched for sanity by at once separating themselves physically and yet reaching out to one another emotionally, calling friends and family, inquiring about their colleagues, and appreciating their personal relationships as the most redeeming element of their existence. Although calamities undoubtedly expose humans’ duplicity, treachery, and cowardice, the MT also revealed their ability to act with nobility.

The global coronavirus pandemic is forcing doctors and nurses to make agonizing decisions of who lives and who dies. It is the toughest and most heartbreaking decision a person could ever have to make. Infected with COVID-19, that is exactly the decision that faced 72-year-old Italian priest Don Giuseppe Berardelli. And in the highest of priestly callings, Berardelli chose to put others’ lives before his own by giving up his ventilator to save the life of a younger person.

We could imagine him saying, as he lay gasping, “I live!”

Let the story be told that even while spreading death and devastation, the Mysterious Traveler encouraged us to look within. No fear, no shame, no war, no famine, no hurricane, flood, plague, or guilt can change who are. The times, they are uncertain. We embrace the uncertainty because we are certain that tomorrow will come. I live, we live, right here and right now. We are in-the-future beings. Let us beat this pandemic, recognize the preciousness—and fragility—of humanity, prepare our scientists and factories for the next one, pour a libation to the future so that our descendants may pour a libation to the past. We give water because we living beings are made of water. In the spirit of all those ancestors in body and spirits seen and unseen, in town and in the bush, in oceans and the deserts, in the plants and animals who gave us life, we pour a libation to you and to the ancestors as yet unborn.