Love is in the air when I arrive at the Newtown Creek Wastewater Treatment Plant for its annual—and hugely popular—Valentine’s Day tour, now in its fourth year.

The hundred or so attendees snatch handfuls of red Hershey’s Kisses from a basket near the door as they take their seats for the introductory presentation, which will explain what happens to New York City’s waste after it disappears down the drain, toilet, and curbside sewer grate.

The talk is led by plant superintendent Zainool Ali, an animated man wearing a bright red sweatshirt, I assume in honor of the occasion.

Arrayed on a table in front of Ali is a rank of plastic bottles of sewage in various stages of treatment. Visitors flock around the table, picking up the bottles, peering through the plastic, and shaking the contents. One bottle contains a hazy fluid flecked with brown bits (“That’s what you flush down the toilet,” Ali explains cheerfully). Another is packed with wads the baby wipes and tampons that get trapped by filters. One is labeled “dewatered sludge ‘cake,’”and it looks almost as rich as the flourless chocolate cake in a February 14 prix fixe.

The backdrop to Ali’s talk is the humming rumble of the plant’s machinery, which operates twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, serving 1.1 million people over 25 square miles and processing 720 million gallons of wastewater each day. It’s one of fourteen wastewater treatment plants in New York City. “The digester just hums love. It grows love,” I hear Ali tell another visitor. Listening to the plant’s sounds is crucial to his job: “You hear a certain sound, smell a certain smell, you know something’s not right,” he tells me later.

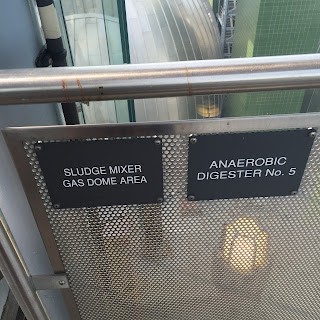

As his audience munches happily on their chocolates, Ali breaks down the wastewater treatment process candidly, interspersed with wry acknowledgment of an uncomfortable topic. In brief, raw wastewater enters the plant, passes through two sets of screens (which catch the baby wipes, street litter, and some solids), then a detritor (a tank that settles heavy grit). The filtered-out solids from the screens and detritors go to landfill. The remaining wastewater passes into an aeration tank, where biological treatment occurs utilizing beneficial bacteria. It then flows into a settling tank, where the solids (known as biosolids) fall to the bottom and get collected for further treatment. The biosolids then go into the digester eggs, the eight gleaming crowns of the plant, which are basically like giant stomachs that digest the sludge and make it safe to return to the environment. The sludge is stabilized by anaerobic bacteria and kept at 98 degrees for fifteen days, producing methane gas, which can be used as fuel. The water that results from the treatment process is disinfected with sodium hypochlorite and then discharged into the East River. The sludge is carted away by boat for further processing and then disposal.

After the presentation, the guests stroll toward the digester eggs, some hand-in-hand.

As we wait in line for the elevator to take us to the viewing platform at the top of the eggs, a sense of camaraderie fills the air. The couple in front of me discusses where they should eat their post-tour lunch. “So who’s your valentine?” a staff member in an EPA windbreaker asks his coworker. “My kids,” she replies. “I’ve been married twenty-eight years. I don’t expect nothin’ no more. Though for Christmas my husband did give me this ring.” She waggles her hand, on which a diamond ring glints. “It’s a Forever Us ring. Because we are ‘forever us.’” She chuckles. “We both work for the city. What can you expect? I don’t ask for much, so I usually get what I want.” “That’s the way to do it!” a visitor chimes in.

On top of the eggs, I ask Ali what is romantic about working here. He replies, “It’s a very tranquil place.” And the catwalks that run along the tops of the digester eggs are indeed tranquil: it’s warm, and there’s that comforting rumbling hum accompanied by a trickling sound of sludge entering the eggs, not unlike the burbling of a mountain stream.

The panoramic view of Brooklyn, Queens, and Manhattan is breathtaking, and couples sidle up to the windows to take it in. “Every year, people come single, leave as couples,” Ali says. “It creates love.”

When asked by another guest what makes sludge sexy, he responds without a pause: “The color, the smooth-like texture.” He gazes proudly at his machinery, which throbs with a heartbeat all its own.

1 thought on “SOUND: Valentine’s Day tour of a sewage treatment plant”

Another fascinating entry. Who knew?