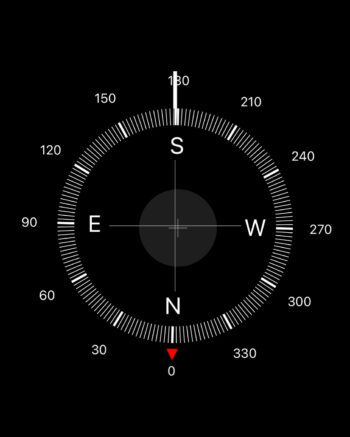

At 12:52 p.m. on March 20, 2023, I’m standing on the gallery overlooking the dark, empty nave at St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery, in the East Village. In approximately fifteen minutes, at 1:07 p.m., it will be solar noon, the time of day when the sun is at its highest point and, today, when it also due south in New York City. This concurrence happens only twice a year: in March and September, on the autumnal and vernal equinoxes. I’m keeping an eye on the stained-glass rose window, which sits high in the south-facing church wall, and watching the time and my compass to track the sunlight as it slips across the glass. In a 2003 New York Times article, I had read that “the noon sun on the equinox … sprays the interior of St. Mark’s with streaks of colored light.” Kathy Chase, then the senior warder of the church, remarked: “At those times of the year, the light in the church is so beautiful.”

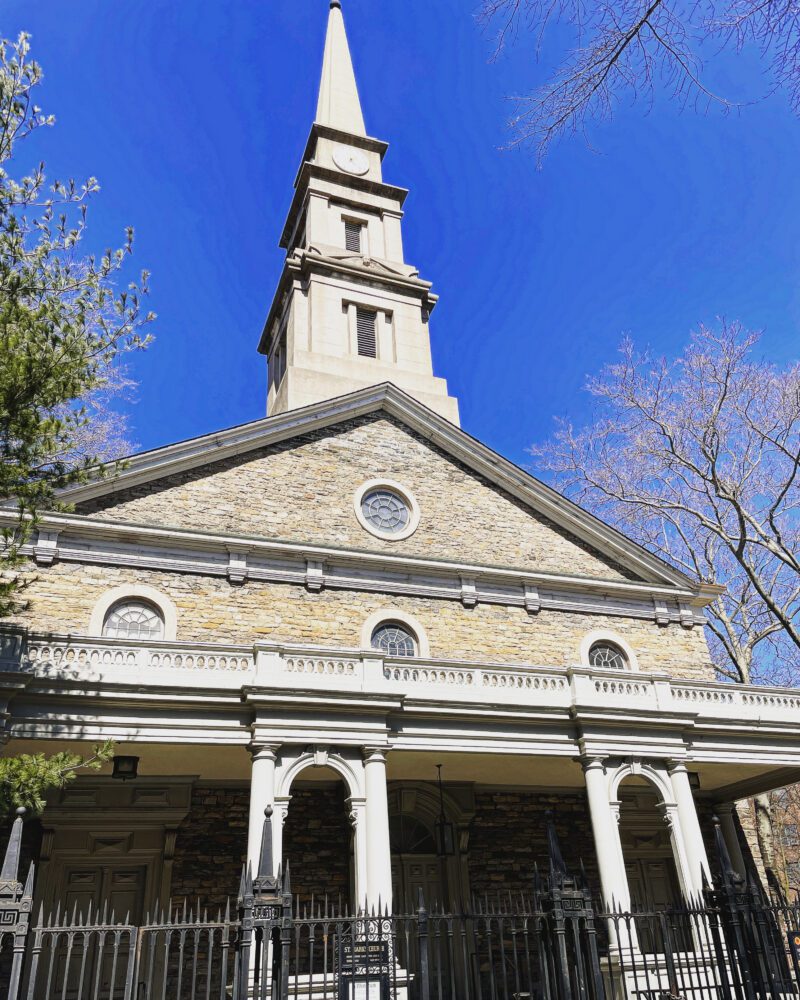

The rose window at St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery, installed in 1983, offers a unique perspective for this twice-yearly solar event. In 1660, Petrus Stuyvesant purchased this plot of bouwerij, or farmland, and erected a family chapel alongside what was then a rural lane—now called Stuyvesant Street—that happened to cut east to west across this part of the island. The church therefore sits askew to the modern Manhattan street grid that grew up around it, in which most streets, avenues, and buildings do not directly face any of the four cardinal directions.

Eventually, the family chapel was sold to the Episcopal Church, and the current building was erected, on the same north–south footprint. With 350 years of history, it’s the second-oldest church building (after Trinity) in the city. Any passerby might notice its placement when strolling up Second Avenue, as if it has been dropped from above onto this plot of grass.

Accompanying me on the balcony is Jimmy, the longtime caretaker of the church, whom I met when I walked through an unmarked side door a few minutes earlier. Despite the fact that I’d apparently interrupted his lunch of Dipsy Doodles, he cheerfully offered to unlock the balcony for me when I told him of my mission. In his forty-five years of working at St. Mark’s, this is the first time someone has shown up on his doorstep on the equinox, looking to see solar noon through the rose window.

It’s not the first time a stranger has shown up on the doorstep of this Episcopal church, however. Churches, of course, are sanctuaries, known for welcoming most anyone. Wearing a Yankees cap, Jimmy regales me with tales of his years working at the church and the characters he has met; his keychain rattles from his belt loop each time he gestures toward the vast space he manages. Jimmy—a Catholic by birth—started working here at age thirteen, in 1978: he had a summer job scraping and repainting the extensive iron fence that surrounds the property.

“Worst job I ever had,” he recalls now with a smile. “The sun’s beating down, we’re working with chisels, the paint’s flying everywhere.” But from that job he worked his way up to other duties and finally to his current post as caretaker. Nowadays, he’s pretty much the only person who’s on site regularly. “If anyone knows this church, it’s me,” he says, explaining some of the building’s hidden features, like an extensive catwalk system built above the cathedral ceiling that allows him to change the lightbulbs without a ladder.

As we chatted, we watched the sun slip from left to right (east to west) across the panes of the south-facing rose window, illuminating each colored segment, like a child filling in a coloring book. By 1 p.m., the window is half-lit, its semicircular reflection cast on the wall and ceiling. Jimmy tells me about the rough days guarding the church during the seventies and eighties, when he had a hard time turning away addicts and others in need, who showed up on the church’s doorstep and sometimes got belligerent. But there were also high points: “All the Beat poets and artists came through here: Allen Ginsberg, Alvin Ailey. I’ve met so many interesting people in this job.”

Jimmy remembers when there used to be a “rickety ladder” in front of these windows that led up to the carillon. One of Jimmy’s many jobs was ringing the church bells, which was done by tugging a thick, heavy rope with knots on it. Jimmy had to climb the rope and swing across the alcove to get the bells to ring at appointed hours. “We always had to run in to ring the bells: ‘Oh, man, we forgot!'” Jimmy says with a laugh. The bells, thankfully, are now on an automated system, and a staircase no longer blocks the windows. Jimmy says he’s lived his whole life in the East Village, in the projects down the street, making for an easy and free commute. “I hate the rat race,” he tells me, tugging at the brim of his cap. It’s 1:07 p.m. The sun, now directly south, floods through all the panes and spills light onto the adjacent walls. At the peak of solar noon, the sunlight limns the circular window like a halo.

Jimmy points out the larger window below the rose window—”That’s a phoenix, with the wings”—that casts a shifting mosaic of colors onto the floor.

The bag of Dipsy Doodles is empty, and Jimmy crumples it in his fist. We take a final look at this dark alcove of the church dappled in colored light. “Amen for churches,” Jimmy says, turning to head back downstairs. Outside, a group of bike messengers huddles on the corner, unaware that the circular window above them, which looks unremarkable from the outside, is creating a secret, ephemeral garden of color indoors, welcoming in the spring.

Sense & the City is a monthly blog exploring the hidden corners of New York City. Each month’s post is devoted to one of the five senses. Receive daily sensory impressions via Instagram @senseandthecity.

Sense & the City is a monthly blog exploring the hidden corners of New York City. Each month’s post is devoted to one of the five senses. Receive daily sensory impressions via Instagram @senseandthecity.