It all began with a tiger-skin rug.

Family legend had it that my grandmother’s suitor had shot it for her in India and offered it as a token of his love. After decades spent in an attic, it needed a little TLC—and that’s when I headed to Middle Village, Queens, to see John Youngaitis, the only taxidermist in the five boroughs.

John has a trim white beard, sharp teeth, and piercing eyes. He took one look at our rug and said it was not worth repairing—yet in the way he cradled the tiger’s head in his tattooed hands, I could see his affection both for animals and for his craft.

I returned a few months later to watch him at work. He greeted me wearing a Harley T-shirt tucked into jeans, exposing his sleeves of tattoos. One project that day was finishing up a scene of a raccoon peering out of the knothole of a tree.

John was puzzled because the client had requested that the tail hang down from below the knothole. “It doesn’t make any sense!” he snorted.

A bifurcated raccoon isn’t the craziest request he’s had. “I’ve got stories,” he told me, reaching for a dusty photo album. He began his career in taxidermy growing up in East New York, as a child apprentice to his father.

He’s fashioned a lamp out of a moose spine, mounted a dog’s head on the dog’s favorite stick, refurbished a raccoon to go in a customer’s kitchen to scare his wife, and taxidermied everything from a baby elephant to a goldfish: “If you can think of it, I’ve worked on it.” John says his favorite jobs are creating scenes, or, as he puts it, “inter-reactions—where things are happening.” Then he gets artistic license.

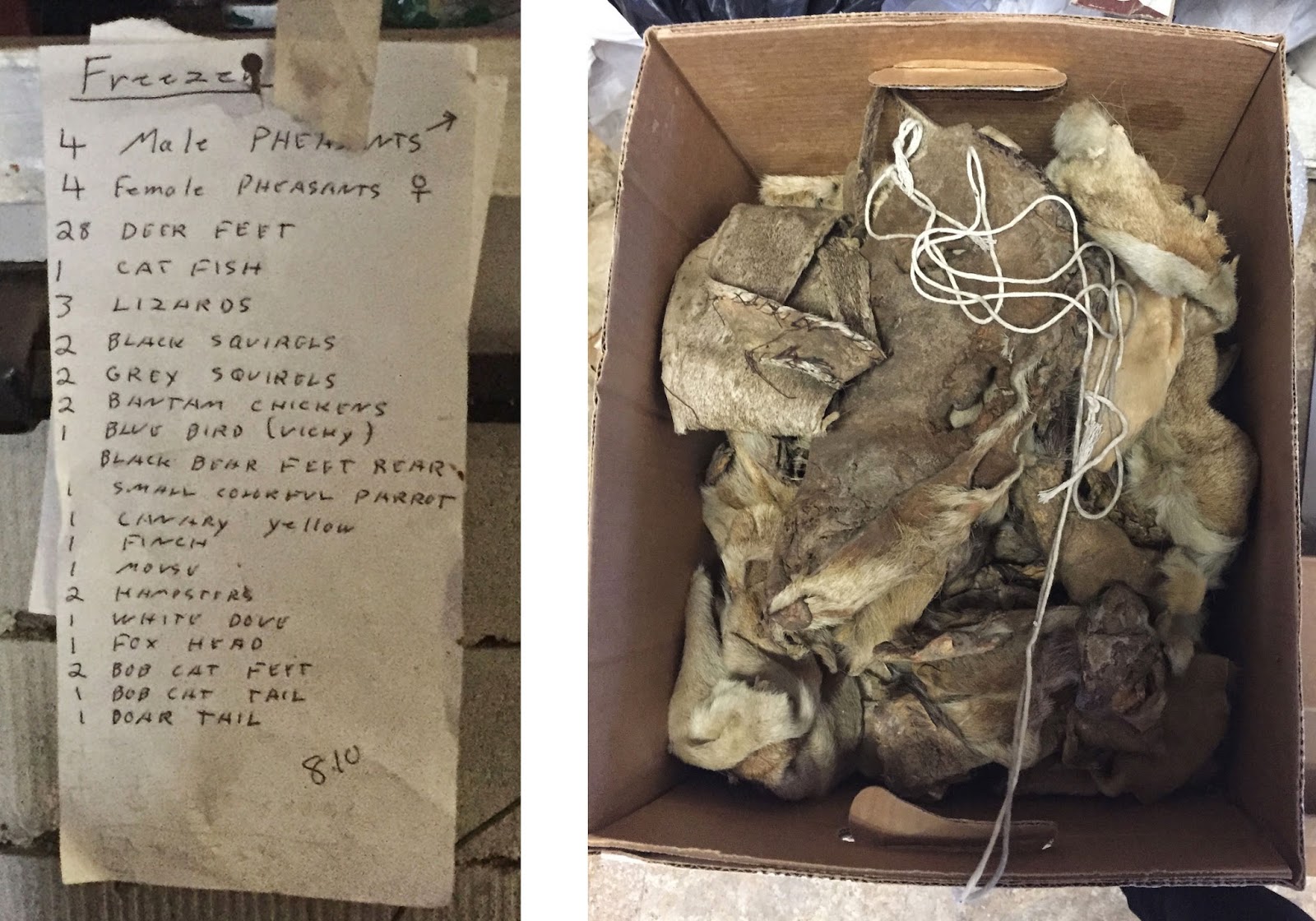

The front of his shop is a showroom of mounts available for sale and for rent. The workroom is in back, behind a curtain, the walls lined with girly posters, tools, and mounted game. Boxes of animal hides rest adjacent to a bench press and the hubcaps of a truck he’s restoring. A list pinned on the wall inventories the animals in his freezer (including “2 bantam chickens” and “1 boar tail”).

John says 80 percent of his business is from hunters; most of the rest is pets and, occasionally, road kill (a remorseful couple recently brought in a coyote they’d hit on the Taconic). People often don’t return to pick up their dogs and cats (“They just get new puppies and kittens”), but bird owners, for some reason, almost always return. “Lots of people have dreams, all these good ideas, then you never see them again,” John says.

His other job for the day is putting the finishing touches on a doe head. John touches up the tear ducts with white paint and combs blue LA Looks hair gel into the fur to smooth it. Clothespins attached to the ears help the hide mold to the plastic form underneath as it dries.

While pet owners bring in photos, hunters have to resort to oral description: they usually want their mount to capture either the way they last saw their prey or its final wall position (gazing toward the couch, for example). John orders all his supplies from Van Dyke’s taxidermy catalog. In its flagged pages, one can find everything from a blesbok form to a warthog eyeball.

John has no lack of work, but nevertheless, he says, “You know what it is? It’s a luxury business. If there’s a water bill, guess who’s going to get paid first? Not Johnny.”

I leave as his cuckoo clock tweets its reconstructed birdsong. The cemetery across the street is reflected in the shopwindow, superimposed on the immortalized creatures inside.