The buildings of Central Park West rose beyond the treetops as Brooke Mellen, the owner of Cultured Forest, a local forest bathing and nature therapy group, instructed us to face each of the four cardinal directions. “Which one feels best?” she asked. This was the opening of what would be a two-hour session of shinrin-yoku, or forest bathing, in a setting far removed from the practice’s roots in 1980s Japan. To me, the most comfortable direction was west, toward the city, with the sunlight on my left arm.

I admit that when I first heard the term “forest bathing,” I pictured myself splayed on the forest floor, gazing up at the treetops, or perhaps sprawled facedown, nuzzling into a bed of moss and pine needles.

So I was surprised to find that, at least in the United States, forest bathing includes few moments of rest. As described by the US-based Association of Nature and Forest Therapy, here shinrin-yoku is “a practice of developing a deepening relationship of reciprocity, in which the forest and the practitioner find a way to work together that supports the wholeness and wellness of each. In forest therapy, there is a clearly defined sequence of guided events that provides structure to the experience, while embracing the many opportunities for creativity and serendipity offered by the forest and the individual inspiration of each guide.”

As we concluded our opening ceremony, peals of laughter and waftings of palo santo incense drifted toward us from a nearby group of French picnickers. Rather than feeling annoyed, I smiled at the thought of this group engaging in their own form of forest therapy, albeit with wine and cheese.

Next, we stopped at the junction of two paths. Brooke had us reach into a bag of stones and select one to infuse with good intentions for the person across from us. Mine was prickly and glinted with mica. We squeezed our rocks and tried to exchange them without opening our eyes. My partner and I crashed into each other, but succeded in passing off our stones. Hers was still warm from her hand.

We strolled on to our next location, observing the movements in the park around us. A dog leaped to catch a squeaky ball. Chipmunks rustled in the underbrush. Bees hovered over flowers. A topless man did calisthenics on a picnic blanket. As usual in the city, everyone was doing their own thing, but on this fall day their disparate activities seemed to be in sync.

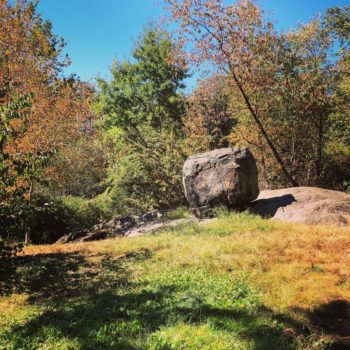

Brooke led us to a secluded grove, where she encouraged us to spend ten minutes immersing ourselves in the forest. Aha! Forest bathing at last. I found a slab of Manhattan schist and lay on my back, inhaling the tannic scent of early autumn and letting the breeze wash across my face.

My reverie did not last long, however, as three men emerged from the trees lugging bulging trash bags. They were soon followed by a man on a bike. “What y’all doing here?” he chastised one member of our group. “I was smokin’ some weed–or I was about to smoke some weed till all y’all came along!” As it turned out, he was a forest bather himself, though perhaps not by choice. The eye of his tiger-print blanket glared out at me from beneath some trees.

After a few more activities, including communing with a tree and throwing stones representing our burdens into a waterfall pool, Brooke had us create Andy Goldsworth–esque art installations in the woods. As I rooted around the forest floor, I kept coming across pieces of litter: four blue cigarillo sheaths, a Magnum condom packet, sublingual film for narcotics overdoses, a Honey Bun wrapper, nickel bags. All seemed to be tokens of the ways humans escape from themselves and their surroundings.

Rather than reject the detritus, I decided to incorporate it into a mandala to honor the dark underbelly of the city’s woodland. Brooke had told me she sometimes arrives ahead of the session to pick up litter from each of the sites, but in this case I was glad she hadn’t. Even if the point of forest bathing is nature appreciation and contemplation, it seemed disingenuous to ignore the reminders of our urban setting.

Our last stop was a boardwalk overlooking a burbling stream, where Brooke unveiled a forest-themed tea ceremony from her backpack, including a thermos of dandelion tea and a box of maple leaf sandwich cookies. She passed around a balm made from hinoki cypress, native to Japan, to rub on our wrists to stimulate our sense of smell. Then she sang a heartfelt rendition of the Beatles’ song “Blackbird,” her voice mingling with the rushing water. An elderly birder with binoculars around his neck paused to listen, smiled, and mentioned a wood thrush he’d spotted near the stream, another urban forest bather making the woods his own.