There now is your insular city of the Manhattoes, belted round by wharves as Indian isles by coral

reefs—commerce surrounds it with her surf. Right and left, the streets take you waterward…. Circumambulate the city of a dreamy Sabbath afternoon. Go from Corlears Hook to Coenties Slip, and from thence, by Whitehall, northward. What do you see?

—Herman Melville, Moby-Dick

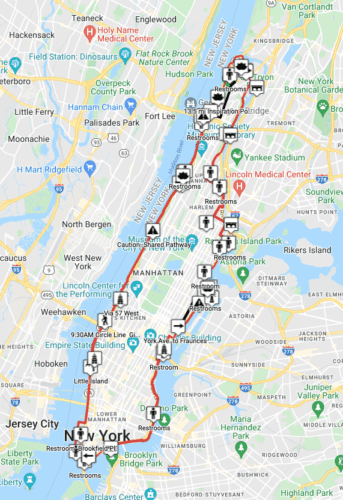

Over the course of two days this May, I completed a thirty-two-mile stroll around the perimeter of Manhattan, staying as close to the shoreline as possible. The route is known as the Great Saunter, and is mapped by Shorewalkers, a nonprofit dedicated to promoting and preserving New York City’s shoreline. This year marked the thirty-fifth Great Saunter, which always takes place the first Saturday of May, starting and ending at the Fraunces Tavern, near Battery Park. This year, however, May 7 dawned rainy and blustery, so I decided to postpone my walk for fairer weather. For those who complete it in one day, the Great Saunter usually takes about eleven hours. The terrain is mostly flat and paved, with the exception of hilly northern Manhattan. On the East Side, the route occasionally veers inland because of construction and an incomplete shoreline trail. I walked the West Side the first day, the East Side the second.

WEST SIDE

Battery Park presented an idyllic scene of New York in spring: toddlers shaking maracas in a music class, a woman strumming a guitar, people doing yoga and playing soccer, a grandmother and granddaughter having a tea party with a Paddington bear. Pulleys clinked against sailboat masts and waves slapped against the piers.

I had been hoping to find hand sanitzer along the way, and was delighted to see an Army National Guard recruitment tent with free Purell set up in the shadow of the Intrepid. “You ever think of joining the army National Guard?” they called after me.

At a beach in the shadows of the West Side Highway, the distant hum of cars and the sulfuric smell of exhaust competed with the saltwater tidal smells off the Hudson and the lap of waves.

At Sixty-Ninth Street, the relics of a transfer bridge rose from the Hudson; here, rail cars were once transferred to rail barges for transport across the river to New Jersey.

In Riverside Park, I was startled to hear frantic meows coming from a plastic bag in a grocery cart alongside the path; the cart’s owner reached inside and murmured, “Tranquilo, tranquilo.” Here the path was inches from the shoreline, strewn with salty driftwood and honey-scented clover.

Farther north, in Riverbank State Park, there were the thwaks and huffs of baseball warm-ups and tinny Latin music from a picnic table, where a group of fishermen taking a lunch break, Chiptle bags hanging from a tree. As I approached the George Washington Bridge, I saw the remains of Uliks Gryka’s Sisyphus Stones installation.

Finally I reached the tip of Manhattan at Spuyten Duyvil Creek, along a woodland trail in Inwood Hill Park. I’d reached mile sixteen of the Saunter—the halfway point—and hobbled over to the A train for the long ride home.

EAST SIDE

After disemarking at 207th Street on Memorial Day, I picked up the trail where I’d left it and made my way over to the path skirting the Harlem River Drive. The air smelled of cut grass. There were fewer people in the dappled shade. Flowers hung from lampposts.

As I passed beneath the trio of bridges spanning Harlem River, I heard the ping-pong of car tires passing overhead and a speedboat buzzed by with women in bikinis splayed across the bow.

People were celebrating Memorial Day by the water. A man caught a fish and presented it proudly to his wife and son, who squealed with delight. Another man walked by with a speaker strapped to his chest that broadcast the sounds of a barking dog. There was the smell of dog poop and charcoal smoke from portable hibachis. I saw a woman with what appeared to be triplets in an inflatable pool. She kicked off a pair of UGG boots and leaned back on the park bench as the children splashed at her feet.

At Carl Schurz Park, near Gracie Mansion, the shoreline path briefly, dramatically improved. East River ferries burbled to and from the landing, the air was fragrant with beach roses, and the nails of tidy, tiny dogs tick-tacked on paving stones.

The path veered inland to Sutton Place, where the steets were so silent I could hear the rustle of people’s gym shorts. One pedestrian overpass strewn with a tide of garbage.

A poet had inscribed a chalk poem in stages along the path, propelling me forward under the blazing sun.

At the edge of Chinatown, in Two Bridges, exercise equipment had been installed beneath the FDR overpass, and neighborhood residents used bikes and ellipitcal trainers, did chin-ups and sit-ups, with views of the river.

On a small sandy beach below the Williamsburg Bridge, shorebirds guarded their nests, gazing out at the river.

Indeed, throughout my two-day journey, I was surprised and moved by the way the shoreline calls to New Yorkers. I saw countless people who, like these birds, were simply sitting at the edge of their island, gazing out at the water. They were not reading, or on their phones, or even talking to one another. They were mostly alone, and mostly just looking. Melville continues:

Posted like silent sentinels all around the town, stand thousands upon thousands of mortal men fixed in ocean reveries…. Nothing will content them but the extremest limit of the land…. Inlanders all, they come from lanes and alleys, streets and avenues—north, east, south, and west. Yet here they all unite.

With thanks to Shorewalkers for the trip planning and to Ann Banks for the Melville inspiration.