Stories from Nurses on the Front Lines

by Samuel Lee

Poetry of Everyday Life

Blogpost #18

Intro

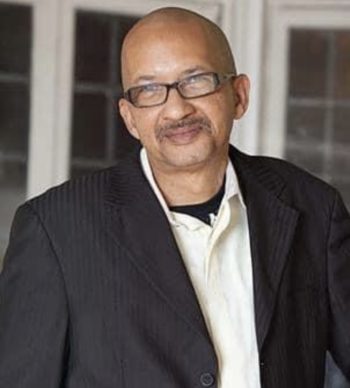

“Being a folklorist is a bit like being a priest,” my close friend Sam Lee once told me, “you have a reverence for things – especially words. I’ve known Sam since my wife Amanda and I came to New York to work as folklorists for the Queens Council on the Arts in 1981. At the time we were doing the project, City Play, and Sam – who also has a reverence for words – told us stories about growing up in Brownsville, Brooklyn. After his mother died when he was 14, he got a job working at Izzy’s poolroom. “I learned to shoot real well, and I would steer people to the numbers writers, the bookies. During the holidays, the numbers men would come around and give people in the neighborhood turkeys and give their children toys. When the cops came around, they would protect them because they didn’t want anybody coming around and taking their turkey man.”

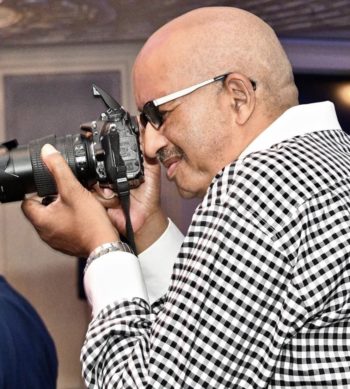

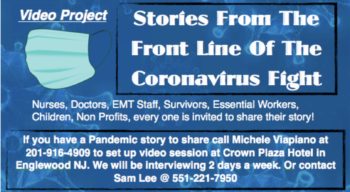

For as long as I’ve Known Sam, he was documenting stories, and a few years ago he told the full story of his childhood on The Moth Radio Hour. Way back in1983, he made a video Rapping with the Rappers interviewing artists including WBLS’ first rapper, deejay Mr Magic, Fearless Four, Spyder D, Female artist D Bora, and LL Cool J to name a few. Currently he runs a storytelling program called Encounters in Black Tradition in Englewood, New Jersey. During the surreal days of the Corona virus, his love of stories emerged as a saving grace for his own well-being and as a window for all of us into what front line nurses braved at the height of the pandemic in New York.

~ Steve Zeitlin

When the virus struck, I was stuck like everyone else. I was in a basement apartment, quarantining myself, watching the news and netflix all day, eating 4 or 5 times a day and getting more and more depressed. I got a call from a friend, Michele Vapiano, who is the manager of the Crowne Plaza Hotel in Englewood, New Jersey. She told me that the hotel was empty and they were giving away a lot of the food, and making rooms available for doctors and front line nurses. I suggested to her that I could set up a video camera in the lobby, and collect some stories.

I was blown away by the stories I was told. The nurses spoke to me like disciplined soldiers sent off to battle. On the front lines, everyone is the same – there’s no color, there’s no white, no black, woman, man, doctor, nurse or room cleaner. They were hugely empathetic human beings. Like medics on the battlefield, they were often ministering to people when they died. As one of the nurses, Melissa Porco, told me, “There’s many nurses including myself that take great pride that we can be there when a person transitions or passes. No matter what race or religion – we try to make that as comforting and as special – it’s truly an honor to be able to do this work with them. Even when the outcome isn’t what we want it to be – we have to accept it. Be with them in that moment and be very present, that’s the key.”

I needed to do these interviews with front line workers for myself – for my own mental health – but also because I realized the stories needed to be told. I have always taken as my tagline some words from the playwright George Bernard Shaw, “I am of the opinion that my life belongs to the community… and as long as I live, it is my privilege to do for it whatever I can. I want to be thoroughly used up when I die, for the harder I work, the more I live.”

The stories of these nurses gave me some badly needed hope. As Michele Porco ended her interview with me, “I would like to say to everybody out there not to give up any hope, that we will get through this. We’re here for you. We won’t leave your side. Hang in. It’ll be OK. Keep hope.”

The very first nurse who came in was Desserie Moran. When I first started interviewing her, I didn’t think this was going to be a quality project – but when I heard the emotion in her narrative, when she started to cry, I realized how deep these stories cut. She told me that when she drove home from work each night she just sat in her car and wept for an hour before she could even open the door to her house. Here is her story.

The very first nurse who came in was Desserie Moran. When I first started interviewing her, I didn’t think this was going to be a quality project – but when I heard the emotion in her narrative, when she started to cry, I realized how deep these stories cut. She told me that when she drove home from work each night she just sat in her car and wept for an hour before she could even open the door to her house. Here is her story.

Desserie Morgan

How has the pandemic changed my life? I don’t sleep like I used to. When I do sleep, I’m dreaming constantly about Covid. When I’m at work I’m worried about my family at home. When I’m home I’m worried about my family at work. I’m a manager as well, and my responsibility is to make sure the people who report to me are safe.

When I’m at home everything has changed, my mental health has changed—hugging and kissing my children is such a natural thing to do, but I find myself feeling stand offish and pulling back – I’m so concerned that I’m going to get them sick. After I do hug them and kiss them I say a prayer – Please God don’t let me give them anything.

I feel like there’s a part of me that’s kind of damaged. That part of my life has changed – I hope not forever. I’m worried when I talk to somebody – I try to get a good look at them and remember them because I may not see them again – because you just don’t know with this thing.

On one of the first pandemic days, the patient in the room with me was not doing great. I was fixing her IV – and as I was fixing her IV her other hand reached over and grabbed mine and I realized she was trying to hold my hand. And I just looked at her and knew she was terrified – her oxygen was de-saturating and I knew she was going to have a rough couple of hours. And there was a very good chance I might be the person or one of the last people to talk to her before she needed to be sedated for intubation. So I tried to make her as calm and as comfortable as I could. I was looking into her eyes and although I was trying to limit my time in the room I knew that she needed me. So I stayed in that room and I held her hand and I told her that I was with her – that she’s not alone. She’s gonna make it through. And she said, “I love you, you’re an angel.” I had to be there for her in that moment.

On one of the first pandemic days, the patient in the room with me was not doing great. I was fixing her IV – and as I was fixing her IV her other hand reached over and grabbed mine and I realized she was trying to hold my hand. And I just looked at her and knew she was terrified – her oxygen was de-saturating and I knew she was going to have a rough couple of hours. And there was a very good chance I might be the person or one of the last people to talk to her before she needed to be sedated for intubation. So I tried to make her as calm and as comfortable as I could. I was looking into her eyes and although I was trying to limit my time in the room I knew that she needed me. So I stayed in that room and I held her hand and I told her that I was with her – that she’s not alone. She’s gonna make it through. And she said, “I love you, you’re an angel.” I had to be there for her in that moment.

My worst day so far – it was on a Sunday – I was a supervisor for the critical care department and I was called in by a frantic critical care physician asking me to find the I-pad immediately and to bring it over to critical care. I told him that patient-relations wasn’t there and there was no one to do it and he said we have about two minutes before this patient passes on us and dies and the family needs to see them. And so I ran to critical care with that I-pad and in that moment I didn’t have the opportunity to know what I was walking into so I was not prepared. And when I got inside and it was just myself and the patient. And I had the I-pad on and I dialed the number and I saw it was a 12 year old boy and his 8 year old sister and their Mom saying goodbye to the patient who was their father. And I have 12-year-old twins and a husband and I couldn’t disconnect from it. And I was staring and the way the I-pad communication works – you see them and they see the patient – and I was staring at them pleading with me to do something about their Daddy and I knew he had minutes, if even. And I kept saying “Honey, talk to your father, and tell him you love him and the Mom was on the other side trying to tell them “say goodbye to Daddy.” And it was so heartbreaking – and I fought back as much as I could. I’m not letting them see my tears. When it was over and I had left the room that same physician came and said “I’m so sorry to do this but we have another one right next door.”

So I went next door, the next room – and I had to do the same thing but this time it was a 19 year old girl and her 15 year old brother saying goodbye to their mother. So I went through that as well. I could not shake that – I could not stop thinking about it for days. I saw their pain, I heard their voices in my head. I couldn’t get past that. So that was definitely the worst day in my life.

The best day is whenever I hear the Rocky song. In my hospital they do an amazing job of celebrating discharges. If a patient is discharged from Covid, they are able to push a button on that person’s way out and it plays the Rocky theme song to just tell them what champions they are – whenever I hear that I’m having the best day.

There is no way in this world I could do anything else and be happy. The team I work with is family – we write our names across our face shields so when we see each other we know we’re family. When this is over everybody on the front lines is going to have to heal mentally. To make sense of what happened, process what we went through. It may be over physically but mentally it has taken a toll. It’s taken a toll.

But I don’t think twice about it. I’m a nurse. That’s what we’re supposed to do – if you’re called to this profession you just feel a need to help people. I don’t feel I’m putting them before my family – I feel like I’m doing for them what I hope somebody would do for my family.

Desserie’s full story on Youtube filmed and edited by Sam Lee can be seen here .